People and labour in Anuar Alimzhanov’s works

Share:

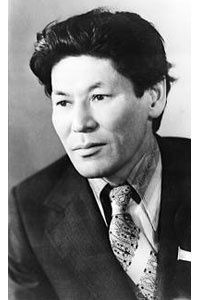

Anuar Turlybekovich Alimzhanov is a well-known Kazakh and Soviet prosaic, writer, publicist and social activist.

Anuar Turlybekovich Alimzhanov is a well-known Kazakh and Soviet prosaic, writer, publicist and social activist.

He was born on 12 May, 1930 in the aul of Karlygash located near Dzhungar mountains. He became an orphan at the early age and was educated in the orphanage. Then, he graduated from the Faculty of Journalism at Kazakh State University in Almaty and worked in the “Literary newspaper” as a correspondent (Middle Asia and Kazakhstan).

Later, he was an Editor-in-Chief at the “Kazakhfilm” studio, a correspondent at “Pravda”, Editor-in-Chief at the newspaper “Kazakh adebieti”.

Since 1970 he was the First Secretary of the Writers’ Union of Kazakhstan. From 1981 to 1991 he was in charge of the Kazakh Agency for Copyright Protection and the president of the Association of Commercial Television and Radio of the Kazakh SSR.

After the first experience in the historic prose, namely, the tale “Suvenir iz Otrara” (“Souvenir from Otrar”, 1966), Anuar Alimzhanov appeals to the huge genre form. One by one come out his historic novels, arranging the whole cycle of the stories about the fate of the Kazakh people a thousand years ago.

Among them the historic works imaging the life of the Kazakhs in early XIX century - “Strela Makhambeta” (“Makhambet’s arrow”, 1969), early XVIII century – “Gonets” (“Rider”, 1974) about the period of time when Kazakhstan started the close association with Russian people, and X century – “Vozvrashenie uchitelya” (“The teachers’ return”, 1979). The last novel in the cycle stood to be “Doroga lyudey” (“People’s way”, 1984) where the author tried to combine the past, present and future.

Working on the novel about Makhambet, Anuar Alimzhanov referred to the oral tales among Kazakh people. Court lifestyle near the khan, trip to Petersburg, initiation to the ideas of December movement, break-up with the khan, participation of Isatay Taimanov (the head of the national liberation movement in West Kazakhstan region in 1836-38 yy.), its defeat – all are deeply depicted by the author.

The same can be said about his tales, where he in a talented way tells about the life of simple and poor people not only of Kazakhstan, but also Africa in which he was quite interested.

A. Alimzhanov’s works are given high estimation in the whole world. They were translated into the languages of the people of the CIS and foreign countries. Among Afro-Asian writers Anuar Alimzhanov was one of the first ones to be honored the “International award of the People’s Republic of Kongo for the fortification of the friendship among the people of Asia and Africa and active contribution in the fight for their independence”. For a number of works on the themes of India in 1969 Anuar Alimzhanov was awarded the prize named after Dzhavakhrlala Neru. He was also awarded the orders of the Friendship of people, “Honor Badge” and medals. Anuar Alimzhanov died on 9 November 1993.

One of his tales about which will be written more in detail is “Povest o pakhare” (“Tale of plougher”). It is rather short and chosen for the description not in vain as not much written about shorter tales of Anuar Alimzhanov.

One of his tales about which will be written more in detail is “Povest o pakhare” (“Tale of plougher”). It is rather short and chosen for the description not in vain as not much written about shorter tales of Anuar Alimzhanov.

The tale is about an outstanding hard-working plougher Ibray-aga being in love with his lifework.

Even he was called (in fact, was) the high performer, lead worker in his field (he specialized in rice growing), innovator he always stayed himself, did not differ from his friends-shepherds of the Aral Sea region. Ibray-aga was squatty, indifferent to the praises, all the clamor and fuss around him. He liked listening to his conversants carefully weighing each word of theirs, but couldn’t stand too talkative people.

He was asked of the secret of growing such big harvest. But he had no secrets. Actually, there was the work, conscientious hard word.

Many years passed since the time he had started to deal with rice growing. He was born on the bank of Syrdaria river and had never left his aul (Kazakh village). He defended his aul in the years of the Civil war. Only once he left his native land for half a year when there was severe hunger during which he managed to save some handfuls of white rice. He saved them for the whole winter and in the spring he planted rice. Since that time his home folks had always had a cup of rice – both in the years of war and peace, in the dry and moist days.

Notwithstanding the fact that he had never left his aul, his fields he was known at the motherland of rice – Burma and Korea, China and India.

Newspapers often (during thirty-five years) wrote about his methods and system. But he himself didn’t pronounce such words as “my method” and “my system”. He asked for advice only from his land, he listened to its breath and applied in his work what was tested, tried and proved with results for tens of years.

He had his own world full with deep thoughts and searches, disappointments and joys, however, he unchangingly stayed calm. Thus, some people thought he was a weird man although it was not like that. And he had a son whom he loved a lot and who was already a grown-up and fought at war. His son was his hope in life whom he saw as the successor of his work. He had trained his son since early years of his life and taught him how to feel the land and how to grow rice in the fields.

But, one day he heard the song of lamentation, it was weeped by his wife. His son, his only son died at war… That night he couldn’t sleep; he didn’t want to believe in that death. He worked hard on the field all night without having a rest and only by the sunrise with bleeding hands, shivering with cold and being ready to drop he slowly went home. It seemed as if the gigantic machine or the army of dzhigits (Kazakh fellows) toiled at the field, that was even and without any bushes and stumps. People were struck with the sight and since that day he had became not Ibray-aga, but Ibray-ata (elder, highly respected man is called “ata”).

The following autumn he collected his first harvest from that field. And it became the sensation for all the rice growers – 172 centner from a ha!

He was a plougher, communist, and a revolutionary who conquered and commanded his fields.

Aging, he gave out his ketmen and reaping hook as the symbol of labour and life to young ploughers, and further to the museum.

After giving up rice growing he never gave up coming to the banks of the river and delighted the sunrise and sunset, saw the work of the young and sometimes grieved or smiled looking at the new sprouts.

His words were, “Heroism is won by life, and fame by labour and talent”. And he wrote the the only one book in his life about his work and friends but stayed modest.

Indeed, he was loved, respected and appreciated by his nobility and huge work.

Anuar Alimzhanov sees things in people’s characters and describes their feelings in a skillful way. He is also good at the presentation of nature, situations and conversations. The reader pictures the story vividly and feels the mood of characters.

The author was one of not many having so many versatile talents and abilities, and at the same time staying so moderate and delicate.

Share: