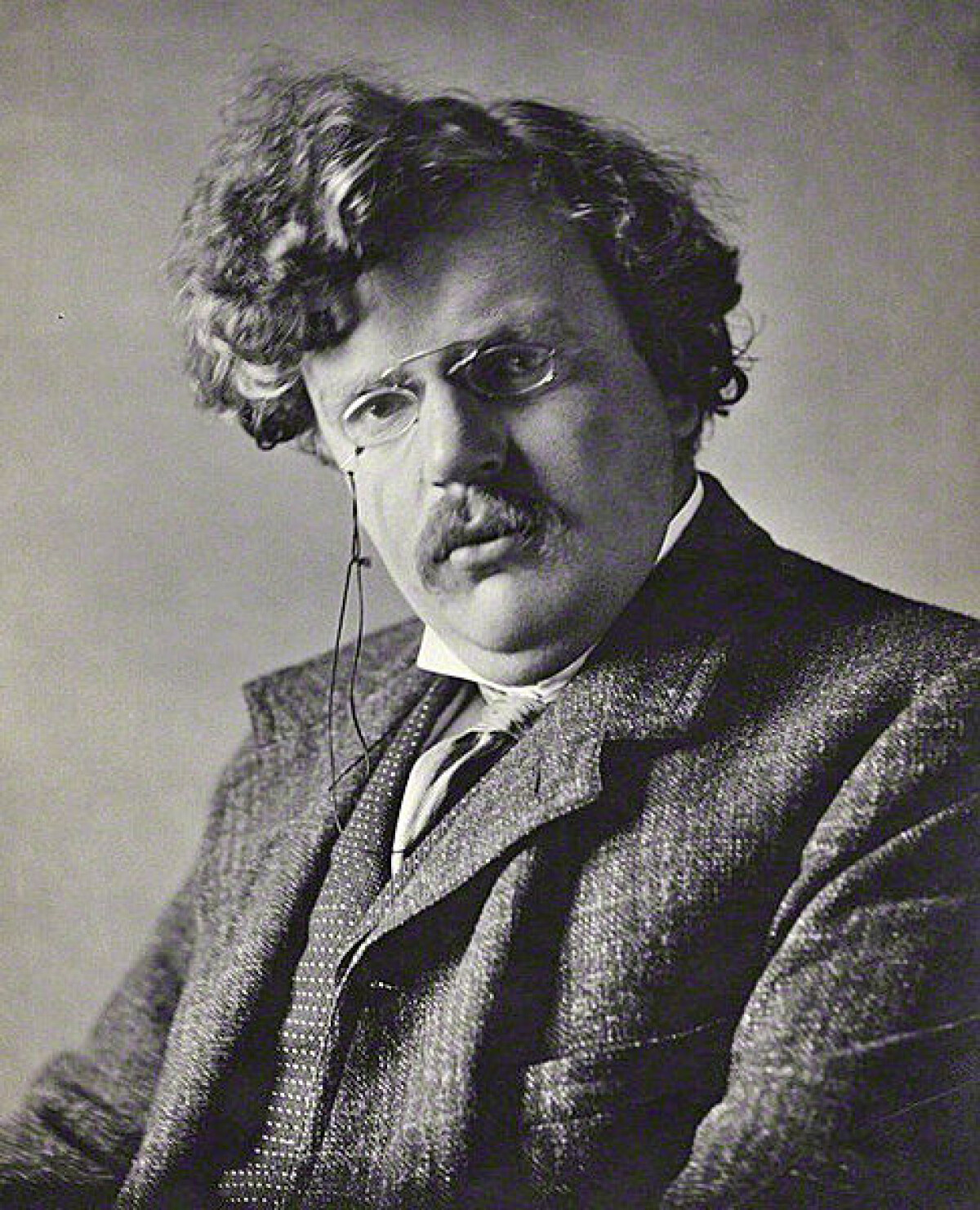

Chesterton Gilbert Keith

Gilbert Keith Chesterton, (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) better known as G.K. Chesterton, was an English writer, lay theologian, poet, dramatist, journalist, orator, literary and art critic, biographer, and Christian apologist. Chesterton is often referred to as the prince of paradox. Time magazine, in a review of a biography of Chesterton, observed of his writing style: Whenever possible Chesterton made his points with popular sayings, proverbs, allegories—first carefully turning them inside out.

Chesterton is well known for his fictional priest-detective Father Brown, and for his reasoned apologetics. Even some of those who disagree with him have recognized the universal appeal of such works as Orthodoxy and The Everlasting Man. Chesterton, as a political thinker, cast aspersions on both Progressivism and Conservatism, saying, The whole modern world has divided itself into Conservatives and Progressives. The business of Progressives is to go on making mistakes. The business of the Conservatives is to prevent the mistakes from being corrected. Chesterton routinely referred to himself as an orthodox Christian, and came to identify this position more and more with Catholicism, eventually converting to Roman Catholicism from High Church Anglicanism. George Bernard Shaw, Chesterton's friendly enemy according to Time, said of him, He was a man of colossal genius. Biographers have identified him as a successor to such Victorian authors as Matthew Arnold, Thomas Carlyle, John Henry Cardinal Newman, and John Ruskin.

Born in Campden Hill in Kensington, London, Chesterton was educated at St Paul's School. He attended the Slade School of Art in order to become an illustrator. The Slade is a department of University College London, where he also took classes in literature, but he did not complete a degree in either subject. In 1896 Chesterton began working for the London publisher Redway, and T. Fisher Unwin, where he remained until 1902. During this period he also undertook his first journalistic work as a freelance art and literary critic. In 1901 he married Frances Blogg, to whom he remained married for the rest of his life. In 1902 the Daily News gave him a weekly opinion column, followed in 1905 by a weekly column in The Illustrated London News, for which he continued to write for the next thirty years.

Chesterton was baptized at the age of one month into the Church of England, though his family themselves were irregularly practising Unitarians. According to Chesterton, as a young man he became fascinated with the occult and, along with his brother Cecil, experimented with Ouija boards.

Chesterton credited his wife Francis with leading him back to Anglicanism, though he began to see Anglicanism as a pale imitation. He entered full communion with the Roman Catholic Church in 1922.

Chesterton early showed a great interest in and talent for art. He had planned to become an artist and his writing shows a vision that clothed abstract ideas in concrete and memorable images. Even his fiction seemed to be carefully concealed parables. Father Brown is perpetually correcting the incorrect vision of the bewildered folks at the scene of the crime and wandering off at the end with the criminal to exercise his priestly role of recognition and repentance. For example, in the story The Flying Stars, Father Brown entreats the character Flambeau to give up his life of crime: There is still youth and honour and humour in you; don't fancy they will last in that trade. Men may keep a sort of level of good, but no man has ever been able to keep on one level of evil. That road goes down and down. The kind man drinks and turns cruel; the frank man kills and lies about it. Many a man I've known started like you to be an honest outlaw, a merry robber of the rich, and ended stamped into slime.

Chesterton was a large man, standing 6 feet 4 inches (1.93 m) and weighing around 21 stone (130 kg). His girth gave rise to a famous anecdote. During World War I a lady in London asked why he was not out at the Front; he replied, If you go round to the side, you will see that I am. On another occasion he remarked to his friend George Bernard Shaw: To look at you, anyone would think a famine had struck England. Shaw retorted, To look at you, anyone would think you have caused it. P. G. Wodehouse once described a very loud crash as a sound like Chesterton falling onto a sheet of tin.

Chesterton usually wore a cape and a crumpled hat, with a swordstick in hand, and a cigar hanging out of his mouth. He had a tendency to forget where he was supposed to be going and miss the train that was supposed to take him there. It is reported that on several occasions he sent a telegram to his wife Frances from some distant (and incorrect) location, writing such things as Am in Market Harborough. Where ought I to be? to which she would reply, Home. Because of these instances of absent-mindedness and of Chesterton being extremely clumsy as a child, there has been speculation that Chesterton had undiagnosed developmental coordination disorder.

Chesterton loved to debate, often engaging in friendly public disputes with such men as George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, Bertrand Russell and Clarence Darrow. According to his autobiography, he and Shaw played cowboys in a silent movie that was never released.

Chesterton died of congestive heart failure on the morning of 14 June 1936, at his home in Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire. His last known words were a greeting spoken to his wife. The homily at Chesterton's Requiem Mass in Westminster Cathedral, London, was delivered by Ronald Knox on 27 June 1936. Knox said, All of this generation has grown up under Chesterton's influence so completely that we do not even know when we are thinking Chesterton. He is buried in Beaconsfield in the Catholic Cemetery. Chesterton's estate was probated at £28,389, approximately equivalent in 2012 terms to £1.3 million.

Telegram sent by Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli (future Pius XII) on behalf of Pope Pius XI to the people of England following the death of Chesterton.

Near the end of his life he was invested by Pope Pius XI as Knight Commander with Star of the Papal Order of St. Gregory the Great (KC*SG). The Chesterton Society has proposed that he be beatified.

Chesterton wrote around 80 books, several hundred poems, some 200 short stories, 4000 essays, and several plays. He was a literary and social critic, historian, playwright, novelist, Catholic theologian and apologist, debater, and mystery writer. He was a columnist for the Daily News, the Illustrated London News, and his own paper, G. K.'s Weekly; he also wrote articles for the Encyclopædia Britannica, including the entry on Charles Dickens and part of the entry on Humour in the 14th edition (1929). His best-known character is the priest-detective Father Brown, who appeared only in short stories, while The Man Who Was Thursday is arguably his best-known novel. He was a convinced Christian long before he was received into the Catholic Church, and Christian themes and symbolism appear in much of his writing. In the United States, his writings on distributism were popularized through The American Review, published by Seward Collins in New York.

Of his nonfiction, Charles Dickens: A Critical Study (1906) has received some of the broadest-based praise. According to Ian Ker (The Catholic Revival in English Literature, 1845–1961, 2003), In Chesterton's eyes Dickens belongs to Merry, not Puritan, England; Ker treats Chesterton's thought in Chapter 4 of that book as largely growing out of his true appreciation of Dickens, a somewhat shop-soiled property in the view of other literary opinions of the time.

Chesterton's writings consistently displayed wit and a sense of humour. He employed paradox, while making serious comments on the world, government, politics, economics, philosophy, theology and many other topics.

Share: