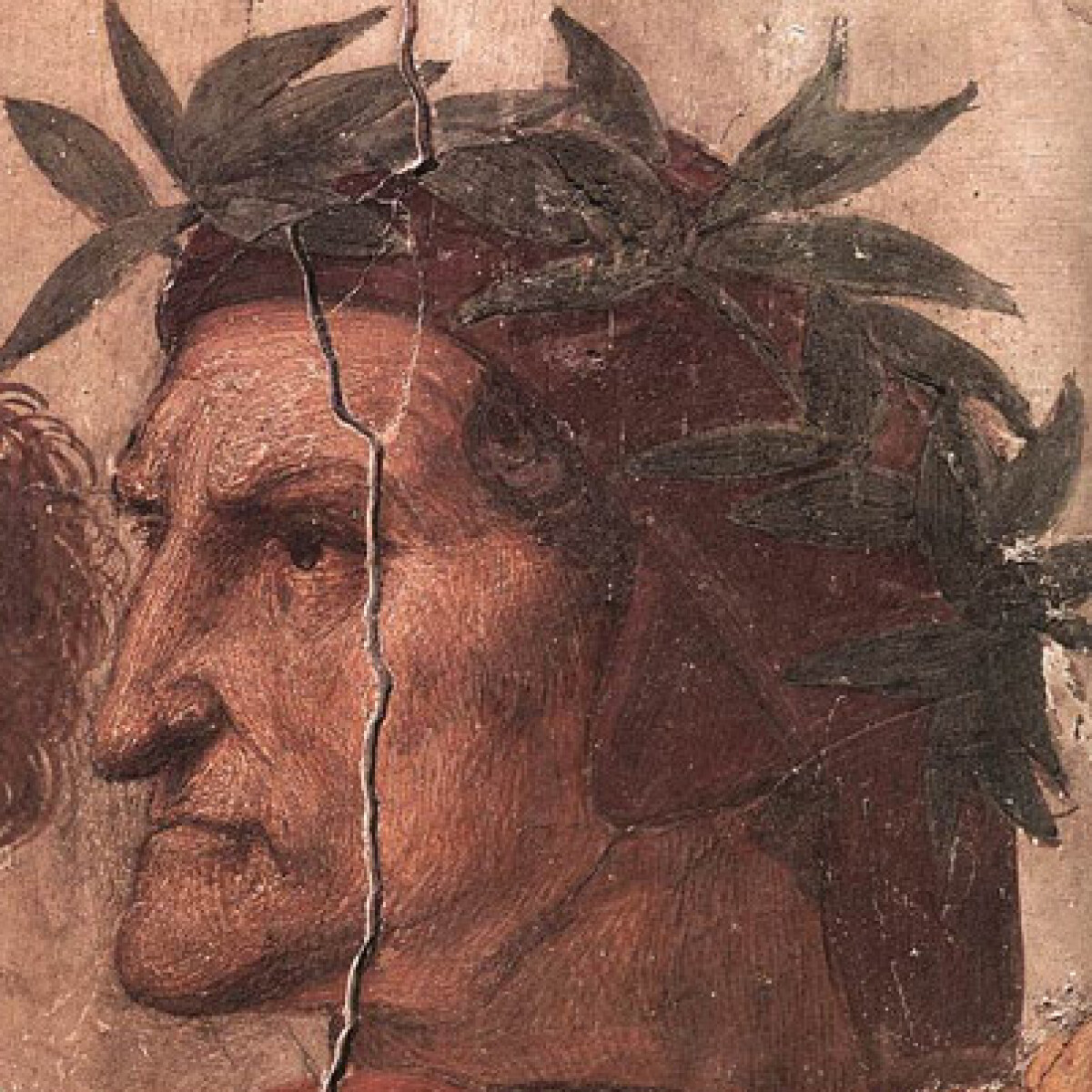

Dante Alighieri

Dante was an Italian poet and moral philosopher best known for the epic poem The Divine Comedy, which comprises sections representing the three tiers of the Christian afterlife: purgatory, heaven, and hell. This poem, a great work of medieval literature and considered the greatest work of literature composed in Italian, is a philosophical Christian vision of mankind’s eternal fate. Dante is seen as the father of modern Italian, and his works have flourished since before his 1321 death.

Dante Alighieri was born in 1265 to a family with a history of involvement in the complex Florentine political scene, and this setting would become a feature in his Inferno years later. Dante’s mother died only a few years after his birth, and when Dante was around 12 years old, it was arranged that he would marry Gemma Donati, the daughter of a family friend. Around 1285, the pair married, but Dante was in love with another woman—Beatrice Portinari, who would be a huge influence on Dante and whose character would form the backbone of Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Dante met Beatrice when she was but nine years old, and he had apparently experienced love at first sight. The pair were acquainted for years, but Dante’s love for Beatrice was “courtly” (which could be called an expression of love and admiration, usually from afar) and unrequited. Beatrice died unexpectedly in 1290, and five years later Dante published Vita Nuova (The New Life), which details his tragic love for Beatrice. (Beyond being Dante’s first book of verse, The New Life is notable in that it was written in Italian, whereas most other works of the time appeared in Latin.)

Around the time of Beatrice’s death, Dante began to immerse himself in the study of philosophy and the machinations of the Florentine political scene. Florence was then was a tumultuous city, with factions representing the papacy and the empire continually at odds, and Dante held a number of important public posts. In 1302, however, he fell out of favor and was exiled for life by the leaders of the Black Guelphs (among them, Corso Donati, a distant relative of Dante’s wife), the political faction in power at the time and who were in league with Pope Boniface VIII. (The pope, as well as countless other figures from Florentine politics, finds a place in the hell that Dante creates in Inferno—and an extremely unpleasant one.) Dante may have been driven out of Florence, but this would be the beginning of his most productive artistic period.

In his exile, Dante traveled and wrote, conceiving The Divine Comedy, and he withdrew from all political activities. In 1304, he seems to have gone to Bologna, where he began his Latin treatise De Vulgari Eloquentia (“The Eloquent Vernacular”), in which he urged that courtly Italian, used for amatory writing, be enriched with aspects of every spoken dialect in order to establish Italian as a serious literary language.

The created language would thus be one way to attempt to unify the divided Italian territories. The work was left unfinished, but it has been influential nonetheless.

In March 1306, Florentine exiles were expelled from Bologna, and by August, Dante ended up in Padua, but from this point Dante’s whereabouts are not know for sure for a few years. Reports place him in Paris at times between 1307 and 1309, but his visit to the city can’t be verified.

In 1308, Henry of Luxembourg was elected emperor as Henry VII. Full of optimism about the changes this election could bring to Italy (in effect, Henry VII could at last restore peace from his imperial throne while at the same time subordinate his spirituality to religious authority), Dante wrote his famous work on the monarchy, De Monarchia,” in three books, in which he claims that the authority of the emperor is not dependent on the pope but descends upon him directly from God. However, Henry’s popularity faded quickly, and his enemies had gathered strength, threatening his ascension to the throne. These enemies, as Dante saw it, were members of the Florentine government, so Dante wrote a diatribe against them and was promptly included on a list of those permanently banned from the city. Around this time, he began writing his most famous work, The Divine Comedy.

In the spring of 1312, Dante seems to have gone with the other exiles to meet up with the new emperor at Pisa (Henry’s rise was sustained, and he was named Holy Roman Emperor in 1312), but again, his exact whereabouts during this period are uncertain. By 1314, however, Dante had completed the Inferno, the segment of The Divine Comedy set in hell, and in 1317 he settled at Ravenna and there completed The Divine Comedy (soon before his death in 1321).

The Divine Comedy is an allegory of human life presented as a visionary trip through the Christian afterlife, written as a warning to a corrupt society to steer itself to the path of righteousness: to remove those living in this life from the state of misery, and lead them to the state of felicity. The poem is written in the first person (from the poet’s perspective) and follows Dante's journey through the three Christian realms of the dead: hell, purgatory, and finally heaven. The Roman poet Virgil guides Dante through hell (Inferno) and purgatory (Purgatorio), while Beatrice guides him through heaven (Paradiso). The journey lasts from the night before Good Friday to the Wednesday after Easter in the spring of 1300 (placing it before Dante’s factual exile from Florence, which looms throughout the Inferno and serves as an undercurrent to the poet’s journey).

The structure of the three realms of the afterlife follows a common pattern of nine stages plus an additional, and paramount, tenth: nine circles of hell, followed by Lucifer’s level at the bottom; nine rings of purgatory, with the Garden of Eden at its peak; and the nine celestial bodies of heaven, followed by the empyrean (the highest stage of heaven, where God resides).

The poem is composed of 100 cantos, written in the measure known as terza rima (thus the divine number 3 appears in each part of the poem), which Dante modified from its popular form so that it might be regarded as his own invention.

Virgil guides Dante through hell and a phenomenal array of sinners in their various states, and Dante and Virgil stop along the way to speak with various characters. Each circle of hell is reserved for those who have committed specific sins, and Dante spares no artistic expense at creating the punishing landscape. For instance, in the ninth circle (reserved for those guilty of treachery), occupants are buried in ice up to their chins, chew on each other and are beyond redemption, damned eternally to their new fate. In the final circle, there is no one left to talk to (as Satan is buried to the waist in ice, weeping from his six eyes and chewing Judas, Cassius and Brutus, the three greatest traitors in history, by Dante’s accounting), and the duo moves on to purgatory.

In the Purgatorio, Virgil leads Dante in a long climb up the Mount of Purgatory, through seven levels of suffering and spiritual growth (an allegory for the seven deadly sins), before reaching the earthly paradise at the top. The poet’s journey here represents the Christian life, in which Dante must learn to reject the earthly paradise he sees for the heavenly one that awaits.

Beatrice, representing divine enlightenment, leads Dante through the Paradiso, up through the nine levels of the heavens (represented as various celestial spheres) to true paradise: the empyrean, where God resides. Along the way, Dante encounters those who on earth were giants of intellectualism, faith, justice and love, such as Thomas Aquinas, King Solomon and Dante’s own great-great-grandfather. In the final sphere, Dante comes face to face with God himself, who is represented as three concentric circles, which in turn represent the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The journey ends here with true heroic and spiritual fulfillment.

Dante’s Divine Comedy has flourished for more than 650 years and has been considered a major work since Giovanni Boccaccio wrote a biography of Dante in 1373. (By 1400, at least 12 commentaries had already been written on the poem’s meaning and significance.) The work is a major part of the Western canon, and T.S. Eliot, who was greatly influenced by Dante, put Dante in a class with only one other poet of the modern world, Shakespeare, saying that they ”divide the modern world between them. There is no third.”

Source: http://www.biography.com/

Share: