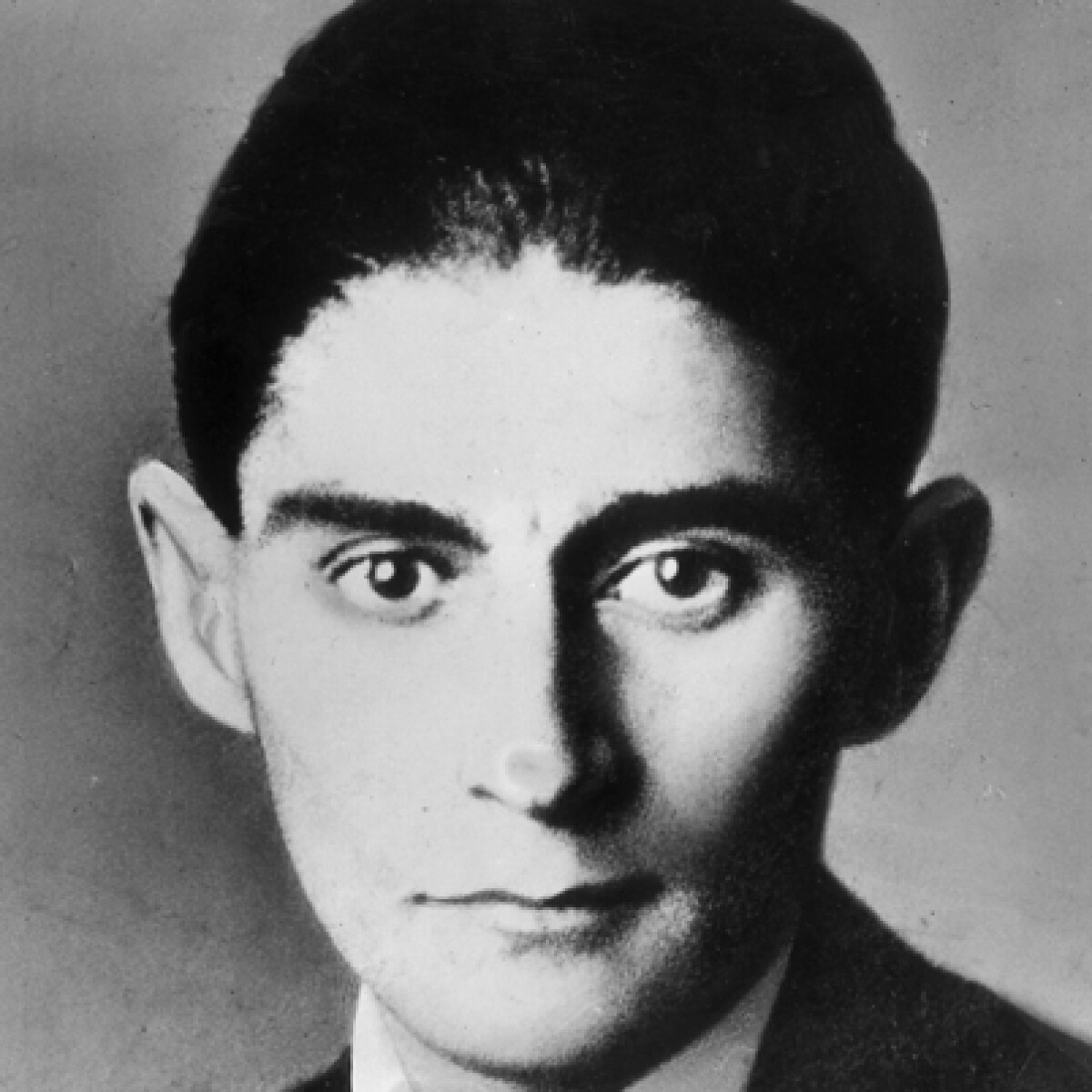

Kafka Franz

Born on July 3, 1883, in Prague, capital of what is now the Czech Republic, writer Franz Kafka grew up in a middle-class Jewish family. After studying law at the University of Prague, he worked in insurance and wrote in the evenings. In 1923, he moved to Berlin to focus on writing, but died of tuberculosis shortly after. His friend Max Brod published most of his work posthumously, such as Amerika and The Castle.

Writer Franz Kafka was the son of a well-to-do Jewish family who was born on July 3, 1883, in Prague, the capital of Bohemia, a kingdom that was a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Tragedy shaped the Kafka home. Franz's two younger brothers, Georg and Heinrich, died in infancy by the time Kafka was 6, leaving the boy the only son in a family that included three daughters.

Kafka had a difficult relationship with both of his parents. His mother, Julie, was a devoted homemaker who lacked the intellectual depth to understand her son's dreams to become a writer. Kafka's father, Hermann, had a forceful personality that often overwhelmed the Kafka home. He was a success in business, making his living retailing men's and women's clothes.

Kafka's father had a profound impact on both Kafka's life and writing. He was a tyrant of sorts, with a wicked temper and little appreciation for his son's creative side. Much of Kafka's personal struggles, in romance and other relationships, came, he believed, in part from his complicated relationship with his father. In his literature, Kafka's characters were often coming up against an overbearing power of some kind, one that could easily break the will of men and destroy their sense of self-worth.

Kafka seems to have derived much of his value directly from to his family, in particular his father. For much of his adult life, he lived within close proximity to his parents.

German was his first language. In fact, despite his Czech background and Jewish roots, Kafka's identity favored German culture.

Kafka was a smart child who did well in school even at the Altstädter Staatsgymnasium, an exacting high school for the academic elite. Still, even while Kafka earned the respect of his teachers, he chafed under their control and the school's control of his life.

After high school Kafka enrolled at the Charles Ferdinand University of Prague, where intended to study chemistry but after just two weeks switched to law. The change pleased his father, and also gave Kafka the time to take classes in art and literature.

In 1906 Kafka completed his law degree and embarked on a year of unpaid work as a law clerk.

After completing his apprenticeship, Kafka found work with an Italian insurance agency in late 1907. It was a terrible fit from the start, with Kafka forced to work a tiring schedule that left little time for his writing.

He lasted at the agency a little less than a year. After turning in his resignation he quickly found a new job with the Workers' Accident Insurance Institute for the Kingdom of Bohemia.

As much as any work could, the job and his employers suited Kafka, who worked hard and became his boss's right-hand man. Kafka remained with the company until 1917, when a bout with tuberculosis forced him to take a sick leave and to eventually retire in 1922.

At work Kafka was a popular employee, easy to socialize with and seen as somebody with a good sense of humor. But his personal life still raged with complications. His inhibitions and insecurities plagued his relationships. Twice he was engaged to marry his girlfriend, Felice Bauer, before the two finally went their separate ways in 1917.

Later, Kafka later fell in love with Dora Dymant (Diamant), who shared his Jewish roots and a preference for socialism. Amidst Kafka's increasingly dire health, the two fell in love and lived together in Berlin. Their relationship largely centered on Kafka's illnesses. For many years, even before he contracted tuberculosis, Kafka had not been well. Constantly strained and stressed, he suffered from migraines, boils, depression, anxiety and insomnia.

Kafka and Dora eventually returned to Prague. In an attempt to overcome his tuberculosis, Kafka traveled to Vienna for treatment at a sanatorium. He died in Kierling, Austria, on June 3, 1924. He was buried beside his parents in Prague's New Jewish Cemetery in Olsanske.

While Kafka strove to earn a living, he also poured himself into his writing work. An old friend named Max Brod would prove crucial in supporting Kafka's literary work both during his life and long after it.

Kafka's celebrity as a writer only came after his death. During his lifetime, he published just a sliver of his overall work.

His most popular and best-selling short story, "The Metamorphosis," was completed in 1912. The story was written from Kafka's third-floor room, which offered a direct view of the Vltava River and its toll bridge.

"I would stand at the window for long periods," he wrote in his diary in 1912, "and was frequently tempted to amaze the toll collector on the bridge below by my plunge."

Kafka followed up "The Metamorphosis" with Mediation, a collection of short stories, in 1913, and then "Before the Law," a short story, a year later.

Even with his worsening health, Kafka continued to write. In 1916 he completed "The Judgment," which spoke directly about the relationship he shared with his father. Later works included "In the Penal Colony" and "A Country Doctor," both finished in 1919.

In 1924, an ill but still working Kafka finished A Hunger Artist, which features four stories that demonstrate the concise and lucid style that marked his writing at the end of his life.

But Kafka, still living with the demons that plagued with him self-doubt, was reluctant to unleash his work on the world. He requested that Brod, who doubled as his literary executor, destroy any unpublished manuscripts.

Fortunately, Brod did not adhere to his friend's wishes and in 1925 published The Trial, a dark, paranoid tale that proved to be the author's most successful novel.

The story centers on the life of Joseph K., who is forced to defend himself in a hopeless court system against a crime that is never revealed to him or to the reader.

The following year, Brod released The Castle, which again railed against a faceless and dominating beauarcracy. In the novel, the protagonist, whom the reader knows only as K., tries to meet with the mysterious authorities who rule his village.

In 1927, the novel Amerika was published. The story hinges on a boy, Karl Rossmann, who is sent by his family to America, where his innocence and simplicity are exploited everywhere he travels. Amerika struck at the same father issues that were prevalent in so much of Kafka's other work. But the story also spoke to Kafka's love of travel books and memoirs (he adored The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin) and his longing to see the world.

In 1931, Brod published the short story "The Great Wall of China," which Kafka had originally crafted 14 years before.

Incredibly, at the time of his death Kafka's name was known only to small group of readers. It was only after he died and Max Brod went against the demands of his friend that Kafka and his work gained fame. His books garnered favor during World War II, especially, and greatly influenced German literature.

As the 1960s took shape and Eastern Europe was under the fist of bureaucratic Communist governments, Kafka's writing resonated particularly strongly with readers. So alive and vibrant were the tales that Kafka spun about man and faceless organizations that a new term was introduced into the English lexicon: "Kafkaesque."

The measure of Kafka's appeal and value as a writer was quantified in 1988, when his handwritten manuscript of The Trial was sold at auction for $1.98 million, at that point the highest price ever paid for a modern manuscript.

The buyer, a West German book dealer, gushed after his purchase was finalized. "This is perhaps the most important work in 20th-century German literature," he said, "and Germany had to have it."

Source: http://www.biography.com/

Share: