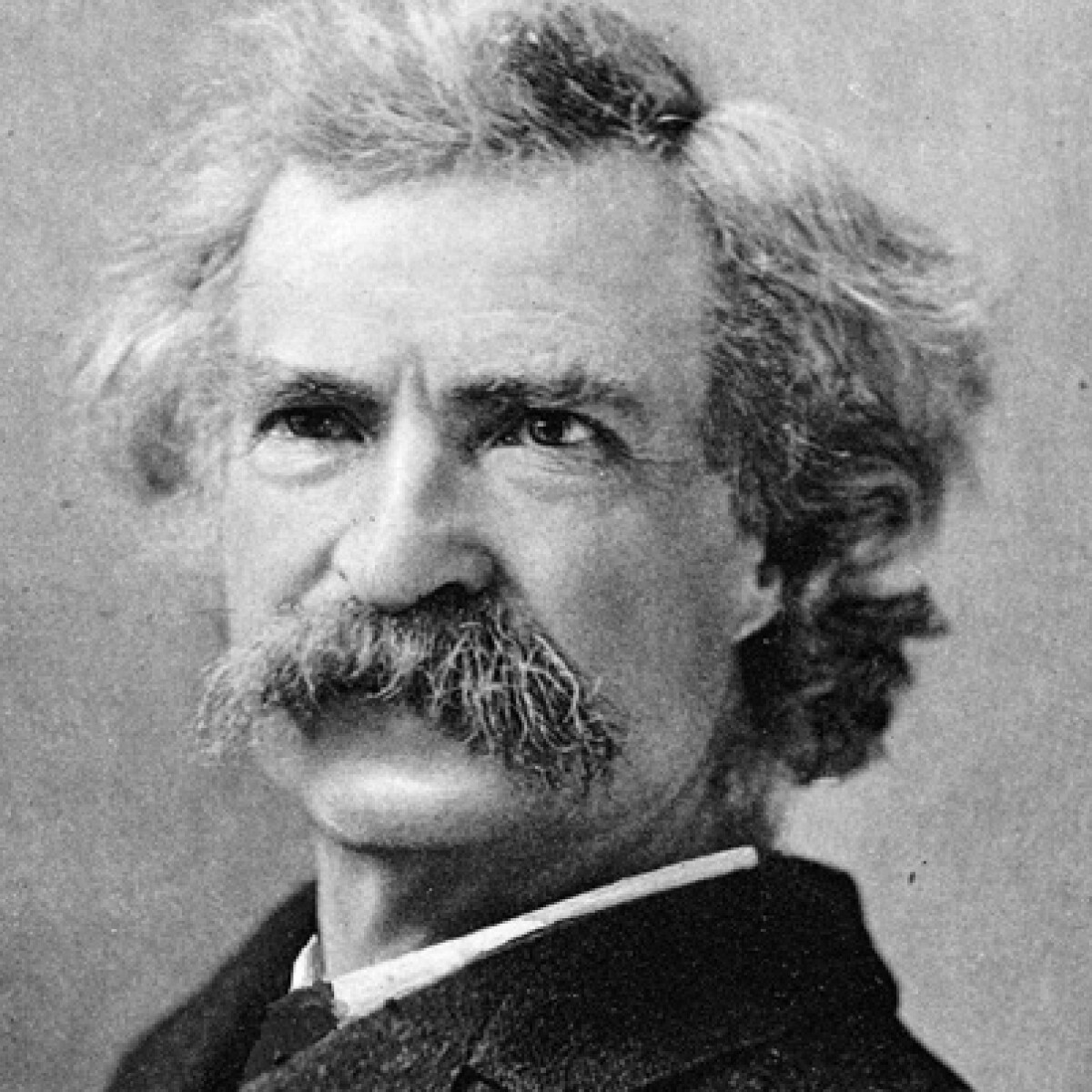

Twain Mark

Born on November 30, 1835, in Florida, Missouri, Samuel L. Clemens wrote under the pen name Mark Twain and went on to pen several novels, including two major classics of American literature, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. He was also a riverboat pilot, journalist, lecturer, entrepreneur and inventor. Twain died on April 21, 1910, in Redding, Connecticut.

Writing grand tales about Tom Sawyer, Huckleberry Finn and the mighty Mississippi River, Mark Twain explored the American soul with wit, buoyancy, and a sharp eye for truth. He became nothing less than a national treasure.

Samuel Langhorne Clemens, better known by his pen name, Mark Twain, was born on November 30, 1835, in the tiny village of Florida, Missouri, the sixth child of John and Jane Clemens. When he was 4 years old, the Clemens clan moved to nearby Hannibal, a bustling town of 1,000 people. John Clemens worked as a storekeeper, lawyer, judge and land speculator, dreaming of wealth but never achieving it, sometimes finding it hard to feed his family. He was an unsmiling fellow; according to one legend, young Sam never saw him laugh. His mother by contrast, was a fun-loving, tenderhearted homemaker who whiled away many a winter's night for her family by telling stories. She became head of the household in 1847 when John died unexpectedly. The Clemens family "now became almost destitute," writes biographer Everett Emerson, and was forced into years of economic struggle—a fact that would shape the career of Mark Twain.

Sam Clemens lived in Hannibal from age 4 to age 17. The town, situated on the Mississippi River, was in many ways a splendid place to grow up. Steamboats arrived there three times a day, tooting their whistles; circuses, minstrel shows, and revivalists paid visits; a decent library was available; and tradesmen such as blacksmiths and tanners practiced their entertaining crafts for all to see. However, violence was commonplace, young Sam witnessed much death. When he was 9 years old he saw a local man murder a cattle rancher, and at 10 he watched a slave die after a white overseer struck him with a piece of iron.

Hannibal inspired several of Mark Twain's fictional locales, including "St. Petersburg" in Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. These imaginary river towns are complex places: sunlit and exuberant on the one hand, but also vipers' nests of cruelty, poverty, drunkenness, loneliness, and life-crushing boredom. All of that had been a part of Sam Clemens' boyhood experience.

Sam kept up his schooling until he was about 12 years old, when—with his father dead and needing to earn his keep—he found employment as an apprentice printer at the Hannibal Courier, which paid him with a meager ration of food. In 1851, at 15, he got a job as a printer and occasional writer and editor at the Hannibal Western Union, a little newspaper owned by his brother, Orion.

Then, in 1857, 21-year-old Clemens fulfilled a dream: He began learning the art of piloting a steamboat on the Mississippi.

A licensed pilot by 1859, he soon found regular employment plying the shoals and channels of the great river. He loved his career—it was exciting, well-paying, and high-status, roughly akin to flying a jetliner today. However, his service was cut short in 1861 by the outbreak of the Civil War, which halted most civilian traffic on the river.

As the war began, the people of Missouri angrily split between support for the Union and the Confederacy. Clemens opted for the latter, joining the Confederate Army in June 1861, but serving for only a couple of weeks until his volunteer unit disbanded.

Where, he wondered then, would he find his future? What venue would bring him both excitement and cash? His answer: the great American West.

In July 1861, Twain climbed onboard a stagecoach and headed for Nevada and California, where he would live for the next five years. At first, he prospected for silver and gold, convinced that he would become the savior of his struggling family and the sharpest-dressed man in Virginia City and San Francisco. But nothing panned out. By the middle of 1862, he was flat broke and in need of a regular job.

He knew his way around a newspaper office, so that September, he went to work as a reporter for the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise. He churned out news stories, editorials and sketches, and along the way, adopted the pen name "Mark Twain"—steamboat slang for 12 feet of water.

Twain became one of the best known storytellers in the West. He honed a distinctive narrative style—friendly, funny, irreverent, often satirical and always eager to deflate the pretentious. He got a big break in 1865, when one of his tales about life in a mining camp, "Jim Smiley and His Jumping Frog," was printed in newspapers and magazines around the country (the story later appeared under various titles). His next step up the ladder of success came in 1867, when he took a five-month sea cruise in the Mediterranean, writing humorously about the sights for American newspapers with an eye toward getting a book out of the trip. And so it came to pass that in 1869 The Innocents Abroad was published, and became a best-seller.

At 34, this westerner—handsome, red-haired, affable, canny, egocentric and ambitious—had become one of the most popular and famous writers in America.

However, Mark Twain worried about being a westerner. In those years, the country's cultural life was dictated by an Eastern establishment centered in New York and Boston—a straight-laced, Victorian, moneyed group that cowed Twain. "An indisputable and almost overwhelming sense of inferiority bounced around his psyche," wrote scholar Hamlin Hill, competing with his aggressiveness and vanity. Twain's fervent wish was to get rich, support his mother, rise socially, and receive what he called "the respectful regard of a high Eastern civilization."

In February 1870, he improved his social status by marrying 24-year-old Olivia (Livy) Langdon, the daughter of a rich New York coal merchant.

Writing to a friend shortly after his wedding, Twain could not believe his good luck: "I have ... the only sweetheart I have ever loved ... she is the best girl, and the sweetest, and gentlest, and the daintiest, and she is the most perfect gem of womankind." Livy, like many people during that time, took pride in her pious, high-minded, genteel approach to life. Twain hoped that she would "reform" him, a mere humorist, from his rustic ways. The couple settled in Buffalo, and later had four children.

Thankfully, Mark Twain's glorious "low-minded" western voice broke through on occasion. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer was published in 1876, and soon thereafter he began writing a sequel, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. (Oddly, the word "The" was not included in the title of book's original edition.) Writing this work, comments biographer Everett Emerson, freed Twain temporarily from the "inhibitions of the culture he had chosen to embrace."

"All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn," Ernest Hemingway wrote in 1935, giving short shrift to Herman Melville and others, but making an interesting point. Hemingway's comment refers specifically to the colloquial language of Twain's masterpiece. For perhaps the first time in America, the vivid, raw, not-so-respectable voice of the common folk was used to create great literature.

Huck Finn required years to conceptualize and write, and Twain often put it aside. In the meantime, he pursued respectability with 1881 publication of The Prince and the Pauper, a charming novel endorsed with enthusiasm by his genteel family and friends. In 1883 he put out Life on the Mississippi, and interesting but safe travel book. When Huck Finn finally was published in 1884, Livy Clemens gave it a chilly reception.

After that business and writing were of equal value to Mark Twain as he set about his cardinal task of earning a lot of money. In 1885, he triumphed as a book publisher by issuing the bestselling memoirs of former President Ulysses S. Grant, who had just died. He lavished many hours on this and other business ventures, and was certain that his efforts would be rewarded with enormous wealth, but he never achieved the success he expected. His publishing house eventually went bankrupt.

Twain's financial failings, reminiscent in some ways to his father's, had serious consequences for his state of mind. They contributed powerfully to a growing pessimism in him, a deep-down feeling that human existence is a cosmic joke perpetrated by a chuckling God. Another cause of his angst, perhaps, was his unconscious anger at himself for not giving undivided attention to his deepest creative instincts, which centered on his Missouri boyhood.

In 1889, Twain published A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, a science-fiction/historical novel about ancient England. His next major work, in 1894, was The Tragedy of Pudd'nhead Wilson, a somber novel that some observers described as "bitter." He also wrote short stories and essays, and several other books, including a study of Joan of Arc.

Some of these later works have enduring merit. His unfinished take The Chronicle of Young Satan has fervent admirers today.

Mark Twain's last fifteen years were filled with public honors, including degrees from Oxford and Yale. Probably the most famous American of the late 19th century, he was much photographed and applauded wherever he went. Indeed, he was one of the most prominent celebrities in the world, traveling widely overseas, including a successful round-the-world lecture tour in 1895-'96, undertaken to pay off his debts.

But while those years were gilded with awards, they also brought him much anguish. Early in their marriage he and Livy had lost their toddler son, Langdon to diphtheria; now in 1896 his favorite daughter, Susy, died at the age of 24 of spinal meningitis. The loss broke his heart, and adding to his grief, he was out of the country when it happened. His youngest daughter, Jean, was diagnosed with sever epilepsy in the mid-1890s; some years later, during epileptic attacks, she twice tried to murder her housekeeper. In 1909, when she was 29 years old, she died of a heart attack. For many years, Twain's relationship with middle daughter Clara was distant and full of quarrels.

In June 1904, Livy died after a long illness. Her husband traveled often while she was sick. "The full nature of his feelings toward her is puzzling," writes scholar R. Kent Rasmussen. "If he treasured Livy's comradeship as much as he often said, why did he spend so much time away from her?" But absent or not, throughout 34 years of marriage, Twain had indeed loved his wife. "Wheresoever she was, there was Eden," he wrote in tribute to her.

Twain became somewhat bitter in his later years, even while projecting an amiable persona to his public. In private he demonstrated a stunning insensitivity to friends and loved ones. "Much of the last decade of his life, he lived in hell," wrote Hamlin Hill. He wrote a fair amount was unable to finish most of his projects. His memory faltered. He had volcanic rages and nasty bouts of paranoia, and he experienced many periods of depressed indolence, which he tried to assuage by smoking cigars, reading in bed, and playing endless hours of billiards and cards.

Samuel Clemens died on April 21, 1910, at the age of 74, at his country home in Redding, Connecticut. He was buried in Elmira, New York.

Share: