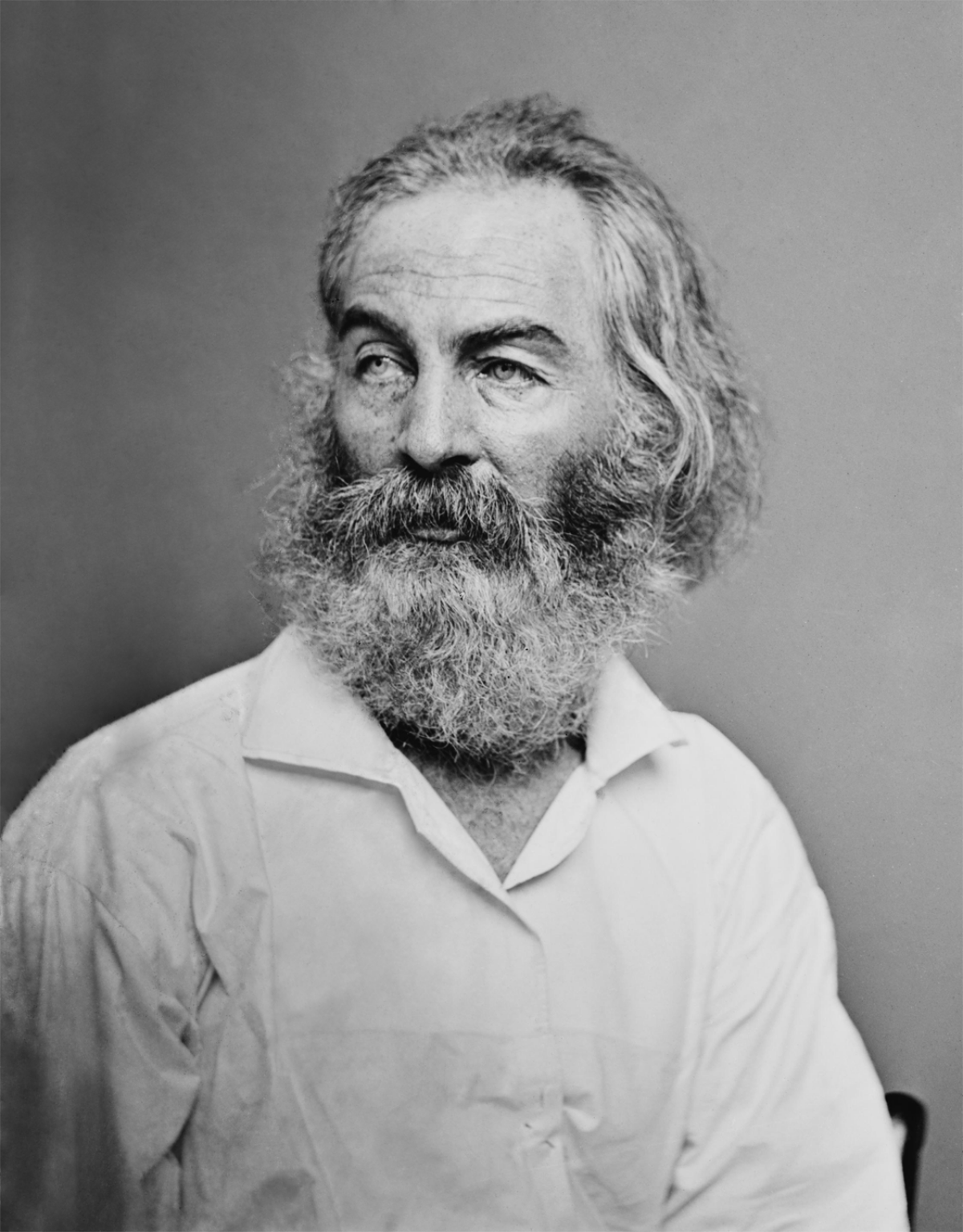

Whitman Walt

Walt Whitman was an American poet whose verse collection Leaves of Grass is a landmark in the history of American literature.

Poet and journalist Walt Whitman was born May 31, 1819 in West Hills, New York. Considered one of America's most influential poet Whitman aimed to transcend traditional epics, eschew normal aesthetic form, and reflect the nature of the American experience and its democracy. In 1855 he self-published the collection Leaves of Grass, now a landmark in American literature.

Walt Whitman was called the "Bard of Democracy". The second of Walter and Louisa Whitman's eight surviving children, he grew up in a family of modest means. While earlier Whitmans had owned a large parcel of farmland, much of it had been sold off by the time young Walt was born. As a result, his father struggled through a series of attempts to recoup some of that earlier wealth, as a farmer, carpenter and real estate speculator.

Whitman's own love for America and its democracy can be at least partially attributed to his upbringing and his parents, who showed their own admiration for their country by naming Walt's younger brothers after their favorite American heroes. The names included George Washington Whitman, Thomas Jefferson Whitman, and Andrew Jackson Whitman. At the age of three, the young Walt Whitman moved with his family to Brooklyn, where his father hoped to take advantage of the economic opportunities in New York City. But his bad investments prevented him from achieving the success he craved. When Walt Whitman was 11, his father, unable to support his family completely on his own, pulled him out of school so he could work. To help put food on the table, Whitman found employment in the printing business.

His father's increasing dependence on alcohol and conspiracy-driven politics, contrasted sharply with his son's preference for a more optimistic course. "I stand for the sunny point of view," he'd say, "the joyful conclusion."

When he was 17, Whitman turned to teaching. His first job was in a one-room schoolhouse in Long Island. Whitman continued teach for another five years, when, in 1841, he set his sights on journalism. He started a weekly paper called the Long-Islander, and later returned to New York City, where he continued his newspaper career. In 1846 he became editor of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, a prominent newspaper.

But Whitman proved to be volatile editor, with a sharp pen and a set of opinions that didn't always align with his bosses o his readers. He backed what some considered radical positions on women's property rights, immigration, and labor issues. He lambasted the infatuation he saw among his fellow New Yorkers with certain European ways and wasn't afraid to go after the editors of other newspapers. Not surprisingly, his job tenure was often short. In a four-year stretch Whitman, was ousted from seven different newspapers.

In 1848 Whitman left New York for New Orleans where he became editor of the Crescent. It was a relatively short stay for Whitman— just three months— but it was where he saw for the first time the wickedness of slavery and the slave trade.

A voracious reader and aspiring poet, Whitman returned to Brooklyn in the autumn of 1848 and started a new "free soil" newspaper called the Brooklyn Freeman.

Over the next seven years, as the nation's temperature over the slavery question continued to rise, Whitman's own anger over the issue elevated as well. He often worried about the impact of slavery on the future of the nation and its democracy. It was during this time that he turned to a simple 3.5 by 5.5 inch notebook, writing down his observations and searching for a poetic voice that could bind together the disparate factions he saw plaguing the country.

In the spring of 1855, Whitman, finally finding the style and voice he'd been searching for, self-published a slim collection of 12 unnamed poems titled Leaves of Grass. Whitman could only afford to print 795 copies of the book. Leaves of Grass marked a radical departure from established poetic norms. Traditional rhyme and meter were discarded in favor of a voice that came at the reader directly, in the first person. On its cover was an image of the bearded poet himself.

The book received little attention at first, though it did catch the eye of fellow poet Ralph Waldo Emerson, who wrote Whitman to praise the collection as "the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom" to come from an American pen.

The following year, Whitman published a revised edition of Leaves of Grass that included 33 poems, including a new piece, "Sun-down Poem" (it was later renamed "Crossing Brooklyn Ferry"), as well as Emerson's letter to Whitman and the poet's long response to him.

Fascinated by this newcomer to the poetry scene, Emerson dispatched writers Henry David Thoreau and Bronson Alcott to Brooklyn to meet Whitman. Whitman, now living at home and truly the man of the homestead (his father passed away in 1855), resided in the attic of the family house.

By this point, Whitman's family life was marked by dysfunction. His brother Andrew was an alcoholic, while his sister was mentally unstable. Whitman himself had to share his bed with his mentally handicapped brother.

Alcott wrote of Whitman, "eyes gray, unimaginative, cautious yet sagacious," wrote Alcott, "his voice deep, sharp, tender sometimes and almost melting. When talking he will recline upon the couch at length, pillowing his head upon his bended arm, and informing you naively how lazy he is, and slow."

Like its earlier edition, this second version of Leaves of Grass failed to gain much commercial traction. In 1860, a Boston publisher issued a third edition of Leaves of Grass. The revised book held some promise, but the start of the Civil War drove the publishing company out of business, furthering Whitman's financial struggles.

In 1862, Whitman moved to Washington D.C. His brother George, who fought for the Union, was being treated in the capital for a wound he suffered in the war. Whitman ended up staying in Washington for the next several years. He found part-time work in the paymaster's office and spent much of the rest of his time visiting wounded soldiers.

This volunteer work proved to be both life-changing and exhausting. By his own rough estimates, Whitman made 600 hospital visits, seeing more than 100,000 patients. The work took a toll physically, but also propelled him to return to poetry. He published an new collection called Drum-Taps, which represented a more solemn realization of what the Civil War meant for those in the thick of it.

This new collection included the poems "Beat! Beat! Drums!" and "Vigil Strange I Kept on the Field One Night." A later edition featured his elegy on President Abraham Lincoln, "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Boom'd."

In the immediate years after the Civil War, Whitman continued to visit wounded veterans. It's during this time that he met Peter Doyle, a young Confederate soldier and train car conductor. Whitman, who had a quiet history of becoming close with younger men, had an instant and intense bond with Doyle. As Whitman's health began to unravel in the 1860s, Doyle helped nurse him back to health.

In Washington, where Whitman eventually found steady work as a clerk at the Indian Bureau of the Department of the Interior, the pace of life that agreed with him. He continued to pursue literary projects, and in 1870 he published two new collections, Democratic Vistas and Passage to India.

But in 1873 his life took a dramatic turn for the worse. In January 1873 he suffered a stroke that left him partially paralyzed. In May he returned home to see his ailing mother, who died just three days after his arrival. Frail himself, Whitman found it impossible to continue with his job in Washington and relocated to Camden, New Jersey, to live with his brother George.

Over the next two decades, Whitman continued to tinker with Leaves of Grass. An 1882 edition of the collection earned the poet some fresh newspaper coverage. That in turn resulted in robust sales, enough so that Whitman was able to buy a modest house of his own in Camden.

These final years proved to be both fruitful and frustrating for Whitman. His life's work received much needed validation in terms of recognition, but the America he saw emerge from the Civil War disappointed him. His health, too, continued to deteriorate.

On March 26, 1892 Walt Whitman passed away in Camden. Right up until the end, he'd continued to work with Leaves of Grass, which during his lifetime had gone through seven editions and expanded to some 300 poems. He was buried in a large mausoleum he had built in Camden's Harleigh Cemetery.

Share: