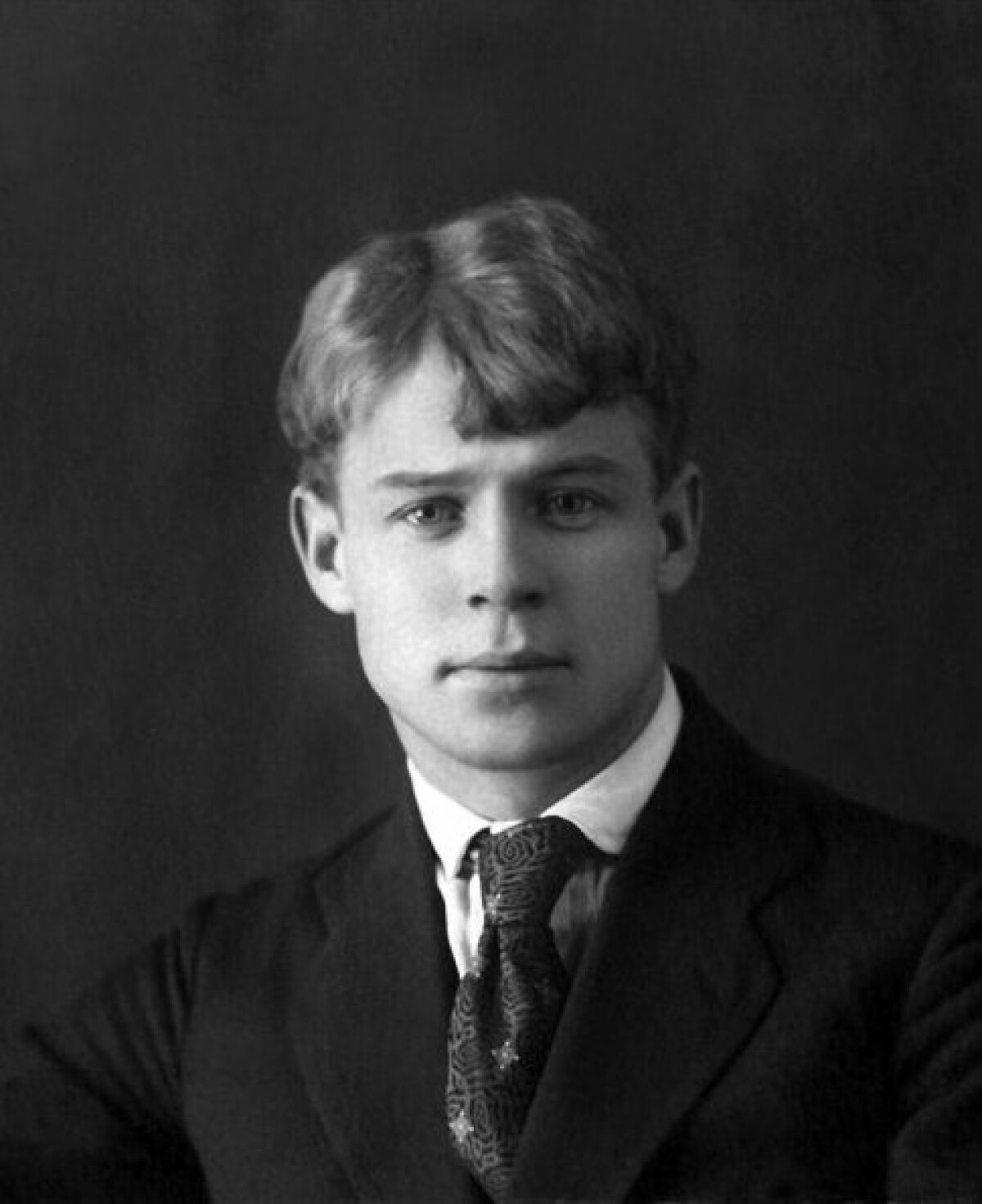

Esenin Sergey

Sergey Esenin was born into a peasant family on 3 October 1895 in the village of Konstantinovo (now Esenino), in the Ryazan region. His parents worked away from home and displayed little concern for their son, who, at the age of two, was put under the care of his maternal grandparents. According to Esenin, no one had a greater influence on him than his grandfather, a member of the Old Believers, a group of Russian religious dissenters who refused to accept the liturgical reforms imposed upon the Russian Orthodox Church by the patriarch of Moscow, Nikon, in the 17th century. Esinin’s grandfather was well versed in religious literature, and successfully fused his spirituality with a practical approach to life; Esenin admired the symmetry of his grandfather’s life and saw him as a true role model.

From 1904 to 1909, Eseninф attended the village school, continuing his education in the church boarding school for prospective teachers. It was during this time that he seriously took up poetry.

Upon the request of his father, a merchant's manager, Esenin moved to Moscow in 1912. In March of 1913, Esenin got a job as a proofreader at Sytin's printing house, where he gained access to a great variety of Russian texts. He joined a group of peasant and proletarian poets known as the Surikov Circle, and occasionally presented his works. In the fall of 1913, Esenin subscribed to the Shanyavsky People's University and attended lectures there on history and philosophy for a year and a half as an external student.

Blessed with good looks and a charming personality, he fell in love frequently and entered quite a number of romantic relationships. He married his first wife, Anna Izriadnova, a co-worker from the publishing house, in the winter of 1913 and lived with her for two years. They had a son, Yury, who in 1937 was persecuted and died in a labor camp.

Esenin's first publication appeared in January of 1914 in the Mirok children's magazine. His poem, “The Birch Tree,” is still a part of the Russian school curriculum and is learned by heart by every elementary school student.

In 1915, Esenin moved to Petrograd (now St. Petersburg), where he thought he would have a greater chance of expanding his literary activity.

In Petrograd, he received a warm welcome from another great poet, Aleksandr Blok, who helped him gain entrance to the city’s literary circles. Esenin met Anna Akhamatova and Nikolay Gumilev and formed a close relationship with the peasant poet Nikolay Kluev, with whom he organized recitals of poems at literary salons, dressing in peasant clothing.

In 1916-17, Esenin served in the military as an orderly on a sanitary train. While working in the infirmary, he had the opportunity to read his poems to the Empress and her daughters, who paid a visit to the facility. Esenin defected from the army shortly after the Revolution of 1917. During the years of the Civil War he extensively toured the country, visiting Murmansk, Archangelsk, the Crimea, the Caucasus, and other places.

In 1916, his first collection of poems, “Radunitsa” (the pagan holiday signifying the commemoration of the dead), was published. In it, Esenin described traditional village life and folk culture, the "wooden Russia" of his childhood, and his pantheistic belief in Nature. In his early poems, Esenin portrayed the Russian countryside melancholically or romantically, and adopted the role of peasant prophet and spiritual leader. The Soviet politician and literary theorist, Leo Trotsky, claimed that Esenin “smelled of medievalism.” On the other hand, Ilya Ehrenburg writes in his memoirs “People, Years, Life” (1960-65), that another prominent writer, Maxim Gorky, was deeply moved and cried when Esenin read him his poems.

In March of 1917, Esenin met his second wife, Zinaida Raikh, an actress. With her he had a daughter, Tatyana, and a son, Konstantin. The marriage however, didn't even last a year.

In 1918, Esenin returned to Moscow, at that time a center of arts and literature. He became a member of the Writer's Union, and with poets Mariengof and Shershenevich, in January of 1919, voiced the declaration of Imaginism, giving birth to a new trend in Russian literature. That same year, in September, he founded his own publishing house under the name Moscow Labor Company of the Artists of Word, which shocked conservative critics with avant-garde poetry and playful blasphemy. He issued several volumes of verse, and contributed to a number of Imaginist collections. Esenin took an active part in the activity of the Imaginist movement: he ran the Imaginist gathering place, the Pegasus Stall Café, and sold books at a specialized Imaginist book store.

Esenin was at first thrilled by the October Revolution and truly hoped it would lead to a better future for the peasantry. These hopes crystallized in the collection “Inoniya” (1918). Later, in “The Stern October Has Deceived Me,” Esenin revealed his disappointment with the Bolsheviks. In his long poetic drama “Pugachyov” (1921-1922), Esenin lauded the spirit of the past and glorified rebellious 18th-century peasant leaders. “Confessions of a Hooligan” (1921), written in the same period, revealed a newly emerged side of Esenin's personality: provocative, vulgar, wounded and anguished.

In the fall of 1921, while visiting his artist friend's workshop, Esenin met the Paris-based American dancer Isadora Duncan, a woman 17 years his senior who spoke no Russian (and he no English). They communicated well enough to be married a few months later on 2 May 1922. In 1922 and 1923 Esenin and his wife toured abroad, stopping in Germany, France, Austria and the United States. Duncan, like many Western artists of the period, was fascinated by the new and promising ideas emanating from the Soviet Union after the Revolution. Esenin had witnessed the devastating effect of these ideas, and wasn't supportive of her enthusiasm, which created tension in their marriage.

Their journey abroad became a disaster for Esenin: his addiction to alcohol had gotten out of control. Often drunk or on drugs, his violent rages resulted in Esenin destroying hotel rooms or causing disturbances in restaurants that received a great deal of publicity in the world press.

In 1923 he returned to Russia, desolated by the trip and suffering from depression and hallucinations. According to his friend Mariengof, Esenin's determination to end his life turned manic: he threw himself in front of a local train, tried to jump from the window of a five story building, and hurt himself with a kitchen knife. In his collection “Love of a Hooligan” (1923), he tried to distance himself from his earlier anarchism and resorted to the healing power of love. Some of his most celebrated lyrics, addressed to his family and village, belong to this period.

During the last years of his life Esenin's depression worsened. Most of the verses in his collection “Moscow of the Taverns” (1924) dealt with his bohemian life in bars, prostitutes, crooks, and other social outcasts seeking consolation from alcohol and daydreaming. In 1924, he re-examined his attitude on the October Revolution and even wrote a eulogistic collection “The Country of Soviets” (1925), dedicated to Lenin. (However he never excelled as a revolutionary poet, or had as much success in the area as Vladimir Mayakovsky.)

Differences in opinions with other Imaginists drove Esenin away from the movement in August of 1924; he had undertaken a trip to the Caucasus, where he produced his collection “Persian Motives” (1925). In the spring of 1925, a highly volatile Esenin met and married his third wife, Sophia Tolstaya, a granddaughter of Leo Tolstoy. She tried to get him help but he suffered a complete mental breakdown and was hospitalized for a month.

In December of that same year, Esenin completed his poem “Black Man,” which he had been working on for two years. The poem, published posthumously, is considered Esenin's most ruthless analysis of his mental disturbances and alcoholic hallucinations.

On his release from a mental facility on 23 December 1925, he escaped from Moscow to Petrograd, where he stayed at the Hotel d'Angleterre. But in Petrograd, he didn't find the peace he was looking for. On the evening of 27 December he wrote the poem "Farewell to you, my friend, farewell to you..." with his own blood, and on the morning of 28 December he was found hanging from the heating pipes of the ceiling... This, in any case, is the official version of his death, but after a great number of very thorough investigations, substantial evidence has been gathered suggesting that Esenin was murdered by the secret police. However, neither of these versions can be proven beyond a doubt.

Communist authorities, who viewed Esenin's poetry with suspicion for its individualism and "hooliganism," feared his works would conflict with the doctrines of Socialist realism, and banned his books. Esenin fell out of favor until after World War II. In the 1960s, his works were reprinted in several editions. Today, Sergey Esenin's poems are very popular. They are a part of the school curriculum and some have been put to music, producing a number of beloved songs.

Share: