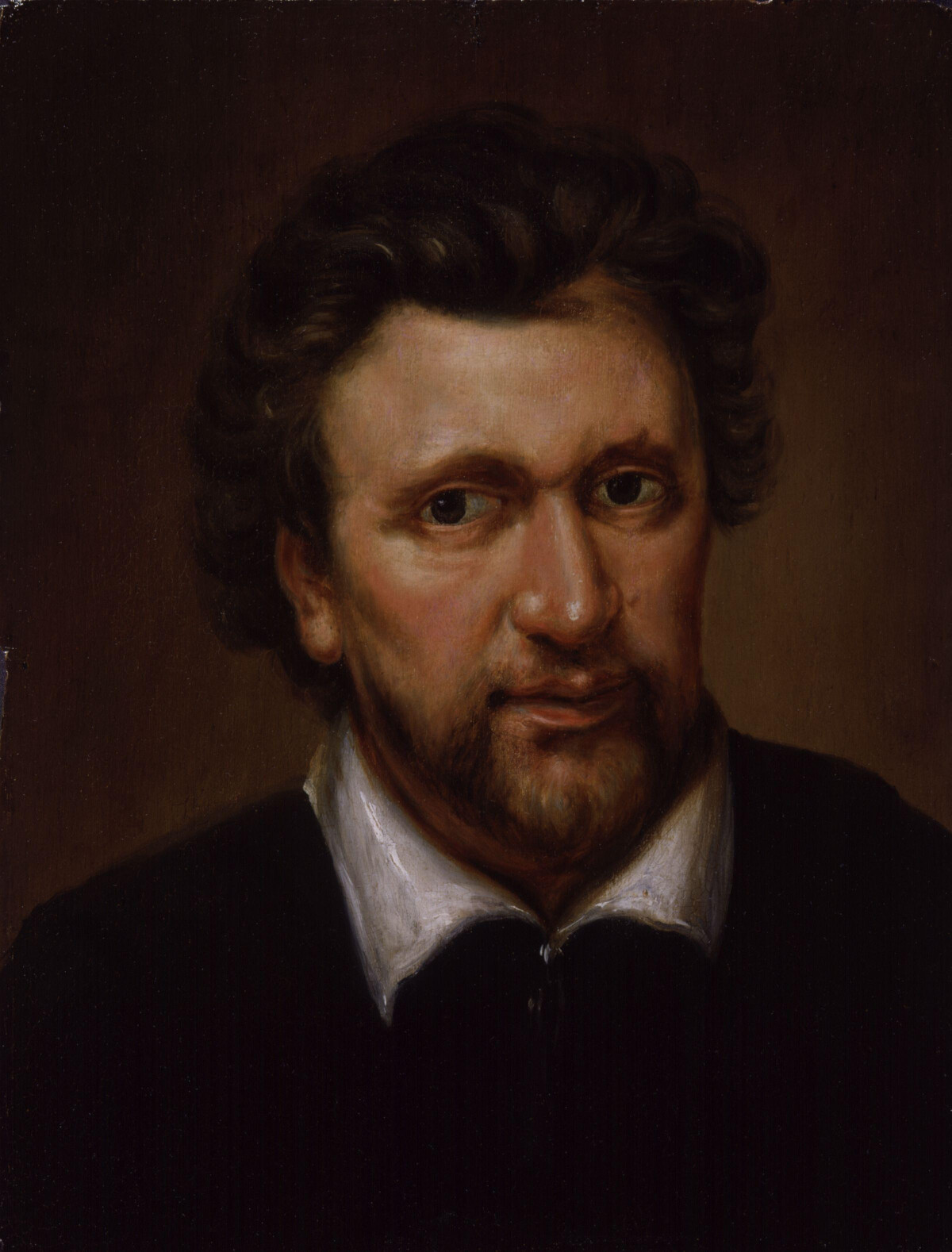

Jonson Benjamin

Benjamin Jonson (circa June 11, 1572 – August 6, 1637) was an English Renaissance dramatist, poet and actor. He is best known for his plays Volpone and The Alchemist and his lyric poems. A man of vast reading and a seemingly insatiable appetite for controversy, Jonson had an unparalleled breadth of influence on Jacobean and Caroline playwrights and poets.

Although he was born in Westminster, London, Jonson claimed his family was of Scottish Border country descent, and this claim may be supported by the fact that his coat of arms bears three spindles or rhombi, a device shared by a Borders family, the Johnstones of Annandale. His father died a month before Ben's birth, and his mother remarried two years later, to a master bricklayer. Jonson attended school in St. Martin's Lane, and was later sent to Westminster School, where one of his teachers was William Camden. Jonson remained friendly with Camden, whose broad scholarship evidently influenced his own style, until the latter's death in 1623. On leaving, Jonson was once thought to have gone on to the University of Cambridge; Jonson himself said that he did not go to university, but was put to a trade immediately: a legend recorded by Fuller indicates that he worked on a garden wall in Lincoln's Inn. He soon had enough of the trade, probably bricklaying, and spent some time in the Low Countries as a volunteer with the regiments of Francis Vere. Jonson reports that while in the Netherlands, he killed an opponent in single combat and stripped him of his weapons. Since the war was otherwise languishing during his service, this fight appears to have been the extent of his combat experience. Ben Jonson married some time before 1594, to a woman he described to Drummond as "a shrew, yet honest." His wife has not been decisively identified, but she is sometimes identified as the Ann Lewis who married a Benjamin Jonson at St Magnus-the-Martyr, near London Bridge. The registers of St. Martin's Church state that his eldest daughter Mary died in November, 1593, when she was only six months old. His eldest son Benjamin died of the plague ten years later (Jonson's epigram On My First Sonne was written shortly after), and a second Benjamin died in 1635. For five years somewhere in this period, Jonson lived separate from his wife, enjoying instead the hospitality of Lord Aubigny.

By the summer of 1597, Jonson had a fixed engagement in the Admiral's Men, then performing under Philip Henslowe's management at The Rose. John Aubrey reports, on uncertain authority, that Jonson was not successful as an actor; whatever his skills as an actor, he was evidently more valuable to the company as a writer.

By this time, Jonson had begun to write original plays for the Lord Admiral's Men; in 1598, he was mentioned by Francis Meres in his Palladis Tamia as one of "the best for tragedy." None of his early tragedies survive, however. An undated comedy, The Case is Altered, may be his earliest surviving play.

In 1597, he was imprisoned for his collaboration with Thomas Nashe in writing the play The Isle of Dogs. Copies of the play were destroyed, so the exact nature of the offense is unknown. However there is evidence that he satirised Lord Cobham. It was the first of several run-ins with the authorities.

In 1598, Jonson produced his first great success, Every Man in his Humour, capitalising on the vogue for humour plays that had been begun by George Chapman with An Humorous Day's Mirth. William Shakespeare was among the first cast. This play was followed the next year by Every Man Out of His Humour, a pedantic attempt to imitate Aristophanes. It is not known whether this was a success on stage, but when published, it proved popular and went through several editions.

That same year, Jonson's irascibility landed him in jail. In a duel on September 22 in Hogsden Fields, he killed one of his fellow-actors, a member of the Admiral's Men named Gabriel Spenser. In prison, Jonson was visited by a Roman Catholic priest, and the result was his conversion to Catholicism, to which he adhered for twelve years. He escaped hanging by pleading benefit of clergy, a legal maneuver which, by Jonson's day, meant only that he was able to gain leniency by reciting a brief bible verse in Latin. The move saved his life but he was forced to forfeit his property and was branded on his left thumb. Neither the affair nor his Catholic conversion seem to have injured Jonson's reputation, as he was back working for Henslowe within months.

In 1601, Jonson was employed by Henslowe to revise Thomas Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy; the version of the play with his additions was published in quarto in 1602.

Jonson's other work for the theater in the last years of Elizabeth I's reign was, unsurprisingly, marked by fighting and controversy. Cynthia's Revels was produced by the Children of the Chapel Royal at Blackfriars Theatre in 1600. It satirized both John Marston, who Jonson believed had accused him of lustfulness, probably in Histrio-Mastix, and Thomas Dekker, against whom Jonson's animus is not known. Jonson attacked the same two poets again in 1601's Poetaster. Dekker responded with Satiromastix, subtitled "the untrussing of the humorous poet." The final scene of this play, while certainly not to be taken at face value as a portrait of Jonson, offers a caricature that is recognizable from Drummond's report: boasting about himself and condemning other poets, criticizing actors' performances of his plays, and calling attention to himself in any available way.

This "War of the Theatres" appears to have been concluded with reconciliation on all sides. Jonson collaborated with Dekker on a pageant welcoming James I to England in 1603, although Drummond reports that Jonson called Dekker a rogue. Marston dedicated The Malcontent to Jonson, and the two collaborated with Chapman on Eastward Ho, a 1605 play whose anti-Scottish sentiment landed both authors in jail for a brief time.

His trouble with English authorities continued. In 1603, he was questioned by the Privy Council about Sejanus, a politically-themed play about corruption in the Roman Empire. He was again in trouble for topical allusions in a play, now lost, in which he took part. After the discovery of the Gunpowder Plot, he appears to have been asked by the Privy Council to attempt to prevail on certain priests connected with the conspirators to cooperate with the government; whatever steps he took in this regard do not appear to have been successful (Teague, 249).

At the beginning of the reign of James I of England in 1603, Jonson joined other poets and playwrights in welcoming the reign of the new King. Jonson quickly adapted himself to the additional demand for masques and entertainments introduced with the new reign and fostered by both the king and his consort, Anne of Denmark.

Jonson flourished as a dramatist during the first decade or so of James's reign; by 1616, he had produced all the plays on which his reputation as a dramatist depends. These include the tragedy of Catiline (acted and printed 1611), which achieved only limited success, and the comedies Volpone, (acted 1605 and printed in 1607), Epicoene, or the Silent Woman (1609), The Alchemist (1610), Bartholomew Fair (1614) and The Devil is an Ass (1616). The Alchemist and Volpone appear to have been successful at once. Of Epicoene, Jonson told Drummond of a satirical verse which reported that the play's subtitle was appropriate, since its audience had refused to applaud the play (i.e., remained silent). Yet Epicoene, along with Bartholomew Fair and (to a lesser extent) The Devil is an Ass have in modern times achieved a certain degree of recognition.

At the same time, Jonson pursued a more prestigious career as a writer of masques for James' court. The Satyr (1603) and The Masque of Blackness (1605) are but two of the some two dozen masques Jonson wrote for James or for Queen Anne; the latter was praised by Swinburne as the consummate example of this now-extinct genre, which mingled speech, dancing, and spectacle. On many of these projects he collaborated, not always peacefully, with designer Inigo Jones. Perhaps partly as a result of this new career, Jonson gave up writing plays for the public theaters for a decade.

1616 saw a pension of 100 marks (about £60) a year conferred upon him, leading some to identify him as England's first Poet Laureate. This sign of royal favour may have encouraged him to publish the first volume of the folio collected edition of his works that year.

In 1618, Ben Jonson set out for his ancestral Scotland on foot. He spent over a year there, and the best-remembered hospitality which he enjoyed was that of the Scottish poet, Drummond of Hawthornden. Drummond undertook to record as much of Jonson's conversation as he could in his diary, and thus recorded aspects of Jonson's personality that would otherwise have been less clearly seen. Jonson delivers his opinions, in Drummond's terse reporting, in an expansive and even magisterial mood. In the postscript added by Drummond, he is described as "a great lover and praiser of himself, a contemner and scorner of others".

While in Scotland, he was made an honorary citizen of Edinburgh. On returning to England, he was awarded an honorary Master of Arts degree from Oxford University.

The period between 1605 and 1620 may be viewed as Jonson's heyday. In addition to his popularity on the public stage and in the royal hall, he enjoyed the patronage of aristocrats such as Elizabeth Sidney (daughter of Philip Sidney) and Lady Mary Wroth. This connection with the Sidney family provided the impetus for one of Jonson's most famous lyrics, the country house poem To Penshurst.

The 1620s begin a lengthy and slow decline for Jonson. He was still well-known; from this time dates the prominence of the Tribe of Ben, those younger poets such as Robert Herrick, Richard Lovelace, and Sir John Suckling who took their bearing in verse from Jonson. However, a series of setbacks drained his strength and damaged his reputation.

Jonson returned to writing regular plays in the 1620s, but these are not considered among his best. They are of significant interest for the study of the culture of Charles I's England. The Staple of News, for example, offers a remarkable look at the earliest stage of English journalism. The lukewarm reception given that play was, however, nothing compared to the dismal failure of The New Inn; the cold reception given this play prompted Jonson to write a poem condemning his audience (the Ode to Myself), which in turn prompted Thomas Carew, one of the "Tribe of Ben," to respond in a poem that asks Jonson to recognize his own decline (MacLean, 88).

The burning of his library in 1623 was a severe blow, as his Execration upon Vulcan shows. In 1628 he became city chronologer of London, succeeding Thomas Middleton; he accepted the salary but did little work for the office. He had suffered a debilitating stroke that year and this position eventually became a sinecure. In his last years he relied heavily for an income on his great friend and patron, William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Newcastle.

The principal factor in Jonson's partial eclipse was, however, the death of James and the accession of King Charles I in 1625. Justly or not, Jonson felt neglected by the new court. A decisive quarrel with Jones harmed his career as a writer of court masques, although he continued to entertain the court on an irregular basis. For his part, Charles displayed a certain degree of care for the great poet of his father's day: he increased Jonson's annual pension to £100 and included a tierce of wine.

Despite the strokes that he suffered in the 1620s, Jonson continued to write. At his death in 1637 he seems to have been working on another play, The Sad Shepherd. Though only two acts are extant, this represents a remarkable new direction for Jonson: a move into pastoral drama.

Jonson was buried in Westminster Abbey, with the inscription, "O Rare Ben Jonson," laid in the slab over his grave. It has been suggested that this could be read "Orare Ben Jonson" (pray for Ben Jonson), which would indicate a deathbed return to Catholicism.

Share: