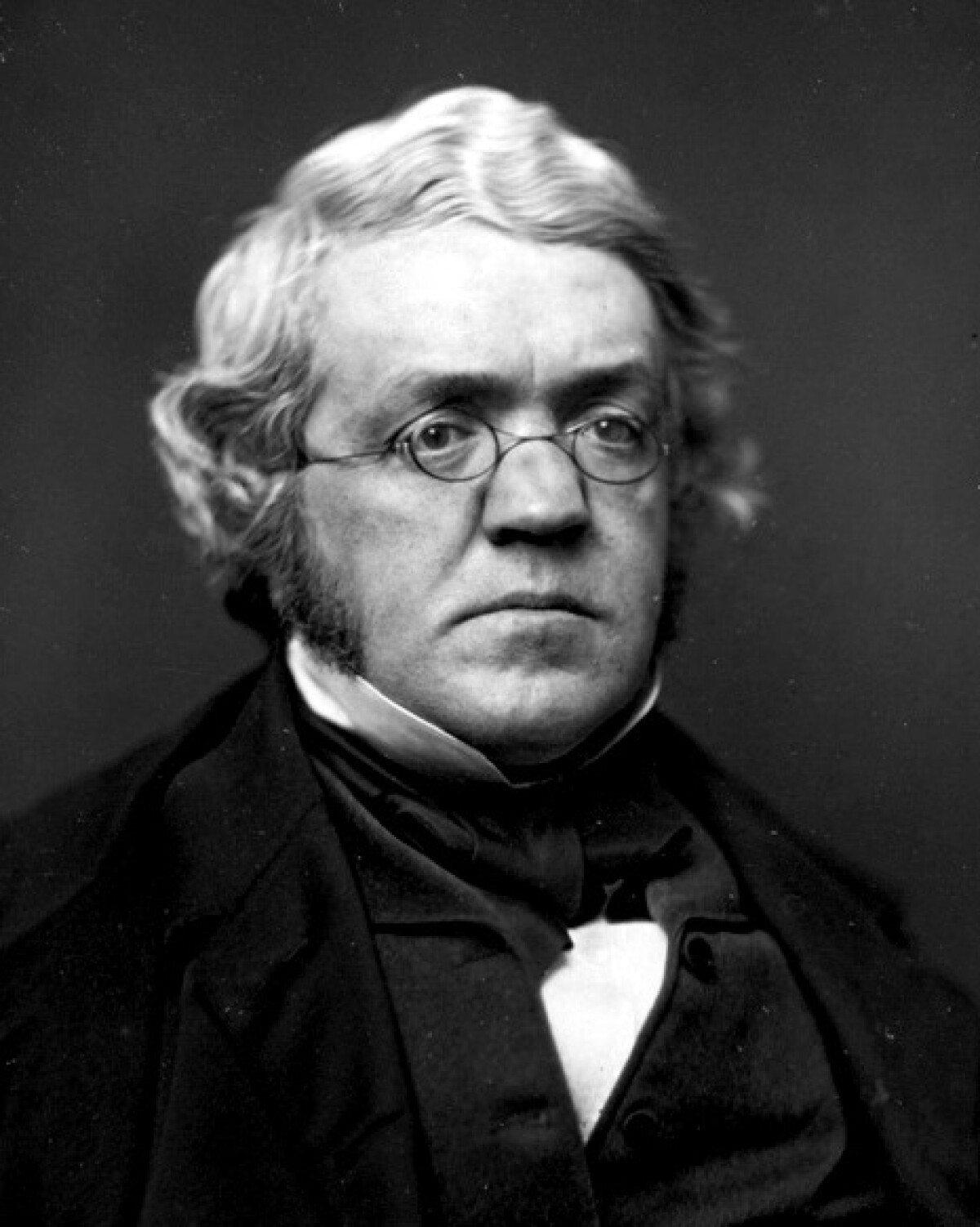

Thackeray William

William Makepeace Thackeray, (born July 18, 1811, Calcutta, India—died Dec. 24, 1863, London, Eng.), English novelist whose reputation rests chiefly on Vanity Fair (1847–48), a novel of the Napoleonic period in England, and The History of Henry Esmond, Esq. (1852), set in the early 18th century.

Thackeray was the only son of Richmond Thackeray, an administrator in the East India Company. His father died in 1815, and in 1816 Thackeray was sent home to England. His mother joined him in 1820, having married (1817) an engineering officer with whom she had been in love before she met Richmond Thackeray. After attending several grammar schools Thackeray went in 1822 to Charterhouse, the London public (private) school, where he led a rather lonely and miserable existence.

He was happier while studying at Trinity College, Cambridge (1828–30). In 1830 he left Cambridge without taking a degree, and during 1831–33 he studied law at the Middle Temple, London. He then considered painting as a profession; his artistic gifts are seen in his letters and many of his early writings, which are amusingly and energetically illustrated. All his efforts at this time have a dilettante air, understandable in a young man who, on coming of age in 1832, had inherited £20,000 from his father. He soon lost his fortune, however, through gambling and unlucky speculations and investments. In 1836, while studying art in Paris, he married a penniless Irish girl, and his stepfather bought a newspaper so that he could remain there as its correspondent. After the paper’s failure (1837) he took his wife back to Bloomsbury, London, and became a hardworking and prolific professional journalist.

Of Thackeray’s three daughters, one died in infancy (1839); and in 1840, after her last confinement, Mrs. Thackeray became insane. She never recovered and long survived her husband, living with friends in the country. Thackeray was, in effect, a widower, relying much on club life and gradually giving more and more attention to his daughters, for whom he established a home in London in 1846. The serial publication in 1847–48 of his novel Vanity Fair brought Thackeray both fame and prosperity, and from then on he was an established author on the English scene.

Thackeray’s one serious romantic attachment in his later life, to Jane Brookfield, can be traced in his letters. She was the wife of a friend of his Cambridge days, and during Thackeray’s “widowerhood,” when his life lacked an emotional centre, he found one in the Brookfield home. Henry Brookfield’s insistence in 1851 that his wife’s passionate but platonic friendship with Thackeray should end was a grief greater than any the author had known since his wife’s descent into insanity.

Thackeray tried to find consolation in travel, lecturing in the United States on The English Humorists of the 18th Century (1852–53; published 1853) and on The Four Georges (1855–56; published 1860). But after 1856 he settled in London. He stood unsuccessfully for Parliament in 1857, quarreled with Dickens, formerly a friendly rival, in the so-called “Garrick Club Affair” (1858), and in 1860 founded The Cornhill Magazine, becoming its editor. After he died in 1863, a commemorative bust of him was placed in Westminster Abbey.

The 19th century was the age of the magazine, which had been developed to meet the demand for family reading among the growing middle class. In the late 1830s Thackeray became a notable contributor of articles on varied topics to Fraser’s Magazine, The New Monthly Magazine, and, later, to Punch. His work was unsigned or written under such pen names as Mr. Michael Angelo Titmarsh, Fitz-Boodle, The Fat Contributor, or Ikey Solomons. He collected the best of these early writings in Miscellanies, 4 vol. (1855–57). These include The Yellowplush Correspondence, the memoirs and diary of a young cockney footman written in his own vocabulary and style; Major Gahagan (1838–39), a fantasy of soldiering in India; Catherine (1839–40), a burlesque of the popular “Newgate novels” of romanticized crime and low life, and itself a good realistic crime story; The History of Samuel Titmarsh and the Great Hoggarty Diamond (1841), which was an earlier version of the young married life described in Philip; and The Luck of Barry Lyndon (1844; revised as The Memoirs of Barry Lyndon, 1856), which is a historical novel and his first full-length work. Barry Lyndon is an excellent, speedy, satirical narrative until the final sadistic scenes and was a trial run for the great historical novels, especially Vanity Fair. The Book of Snobs (1848) is a collection of articles that had appeared successfully in Punch (as “The Snobs of England, by One of Themselves,” 1846–47). It consists of sketches of London characters and displays Thackeray’s virtuosity in quick character-drawing. The Rose and the Ring, Thackeray’s Christmas book for 1855, remains excellent entertainment, as do some of his verses; like many good prose writers, he had a facility in writing light verse and ballads.

With Vanity Fair (1847–48), the first work published under his own name, Thackeray adopted the system of publishing a novel serially in monthly parts that had been so successfully used by Dickens. Set in the second decade of the 19th century, the period of the Regency, the novel deals mainly with the interwoven fortunes of two contrasting women, Amelia Sedley and Becky Sharp. The latter, an unprincipled adventuress, is the leading personage and is perhaps the most memorable character Thackeray created. Subtitled “A Novel Without a Hero,” the novel is deliberately antiheroic: Thackeray states that in this novel his object is to “indicate . . . that we are for the most part . . . foolish and selfish people . . . all eager after vanities.”

The wealthy, wellborn, passive Amelia Sedley and the ambitious, energetic, scheming, provocative, and essentially amoral Becky Sharp, daughter of a poor drawing master, are contrasted in their fortunes and reactions to life, but the contrast of their characters is not the simple one between moral good and evil—both are presented with dispassionate sympathy. Becky is the character around whom all the men play their parts in an upper middle-class and aristocratic background. Amelia marries George Osborne, but George, just before he is killed at the Battle of Waterloo, is ready to desert his young wife for Becky, who has fought her way up through society to marriage with Rawdon Crawley, a young officer of good family. Crawley, disillusioned, finally leaves Becky, and in the end virtue apparently triumphs, Amelia marries her lifelong admirer, Colonel Dobbin, and Becky settles down to genteel living and charitable works.

The rich movement and colour of this panorama of early 19th-century society make Vanity Fair Thackeray’s greatest achievement; the narrative skill, subtle characterization, and descriptive power make it one of the outstanding novels of its period. But Vanity Fair is more than a portrayal and imaginative analysis of a particular society. Throughout we are made subtly aware of the ambivalence of human motives, and so are prepared for Thackeray’s conclusion: “Ah! Vanitas Vanitatum! Which of us is happy in this world? Which of us has his desire, or having it, is satisfied?” It is its tragic irony that makes Vanity Fair a lasting and insightful evaluation of human ambition and experience.

Successful and famous, Thackeray went on to exploit two lines of development opened up in Vanity Fair: a gift for evoking the London scene and for writing historical novels that demonstrate the connections between past and present. He began with the first, writing The History of Pendennis (1848–50), which is partly fictionalized autobiography. In it, Thackeray traces the youthful career of Arthur Pendennis—his first love affair, his experiences at “Oxbridge University,” his working as a London journalist, and so on—achieving a convincing portrait of a much-tempted young man.

Turning to the historical novel, Thackeray chose the reign of Queen Anne for the period of The History of Henry Esmond, Esq., 3 vol. (1852). Some critics had thought that Pendennis was a formless, rambling book. In response, Thackeray constructed Henry Esmond with great care, giving it a much more formal plot structure. The story, narrated by Esmond, begins when he is 12, in 1691, and ends in 1718. Its complexity of incident is given unity by Beatrix and Esmond, who stand out against a background of London society and the political life of the time. Beatrix dominates the book. Seen first as a charming child, she develops beauty combined with a power that is fatal to the men she loves. One of Thackeray’s great creations, she is a heroine of a new type, emotionally complex and compelling, but not a pattern of virtue. Esmond, a sensitive, brave, aristocratic soldier, falls in love with her but is finally disillusioned. Befriended as an orphan by Beatrix’ parents, Lord and Lady Castlewood, Henry initially adores Lady Castlewood as a mother and eventually, in his maturity, marries her.

Written in a pastiche of 18th-century prose, the novel is one of the best evocations in English of the atmosphere of a past age. It was not well received, however—Esmond’s marriage to Lady Castlewood was criticized. George Eliot called it “the most uncomfortable book you can imagine.” But it has come to be accepted as a notable English historical novel.

Thackeray returned to the contemporary scene in his novel The Newcomes (1853–55). This work is essentially a detailed study of prosperous middle-class society and is centred upon the family of the title. Col. Thomas Newcome returns to London from India to be with his son Clive. The unheroic but attractive Clive falls in love with his cousin Ethel, but the love Clive and Ethel have for each other is fated to be unhappily thwarted for years because of worldly considerations. Clive marries Rose Mackenzie; the selfish, greedy, cold-hearted Barnes Newcome, Ethel’s father and head of the family, intrigues against Clive and the Colonel; and the Colonel invests his fortune imprudently and ends as a pensioner in an almshouse. Rose dies in childbirth, and the narrative ends with the Colonel’s death. This deathbed scene, described with deep feeling that avoids sentimentality, is one of the most famous in Victorian fiction. In a short epilogue Thackeray tells us that Clive and Ethel eventually marry—but this, he says, is a fable.

The Virginians (1857–59), Thackeray’s next novel, is set partly in America and partly in England in the latter half of the 18th century and is concerned mostly with the vicissitudes in the lives of two brothers, George and Henry Warrington, who are the grandsons of Henry Esmond, the hero of his earlier novel. Thackeray wrote two other serial novels, Lovel the Widower (1860) and The Adventures of Philip (1861–62). He died after having begun writing the novel Denis Duval.

In his own time Thackeray was regarded as the only possible rival to Dickens. His pictures of contemporary life were obviously real and were accepted as such by the middle classes. A great professional, he provided novels, stories, essays, and verses for his audience, and he toured as a nationally known lecturer. He wrote to be read aloud in the long Victorian family evenings, and his prose has the lucidity, spontaneity, and pace of good reading material. Throughout his works, Thackeray analyzed and deplored snobbery and frequently gave his opinions on human behaviour and the shortcomings of society, though usually prompted by his narrative to do so. He examined such subjects as hypocrisy, secret emotions, the sorrows sometimes attendant on love, remembrance of things past, and the vanity of much of life—such moralizing being, in his opinion, an important function of the novelist. He had little time for such favourite devices of Victorian novelists as exaggerated characterization and melodramatic plots, preferring in his own work to be more true to life, subtly depicting various moods and plunging the reader into a stream of entertaining narrative, description, dialogue, and comment.

Thackeray’s high reputation as a novelist continued unchallenged to the end of the 19th century but then began to decline. Vanity Fair is still his most interesting and readable work and has retained its place among the great historical novels in the English language.

Share: