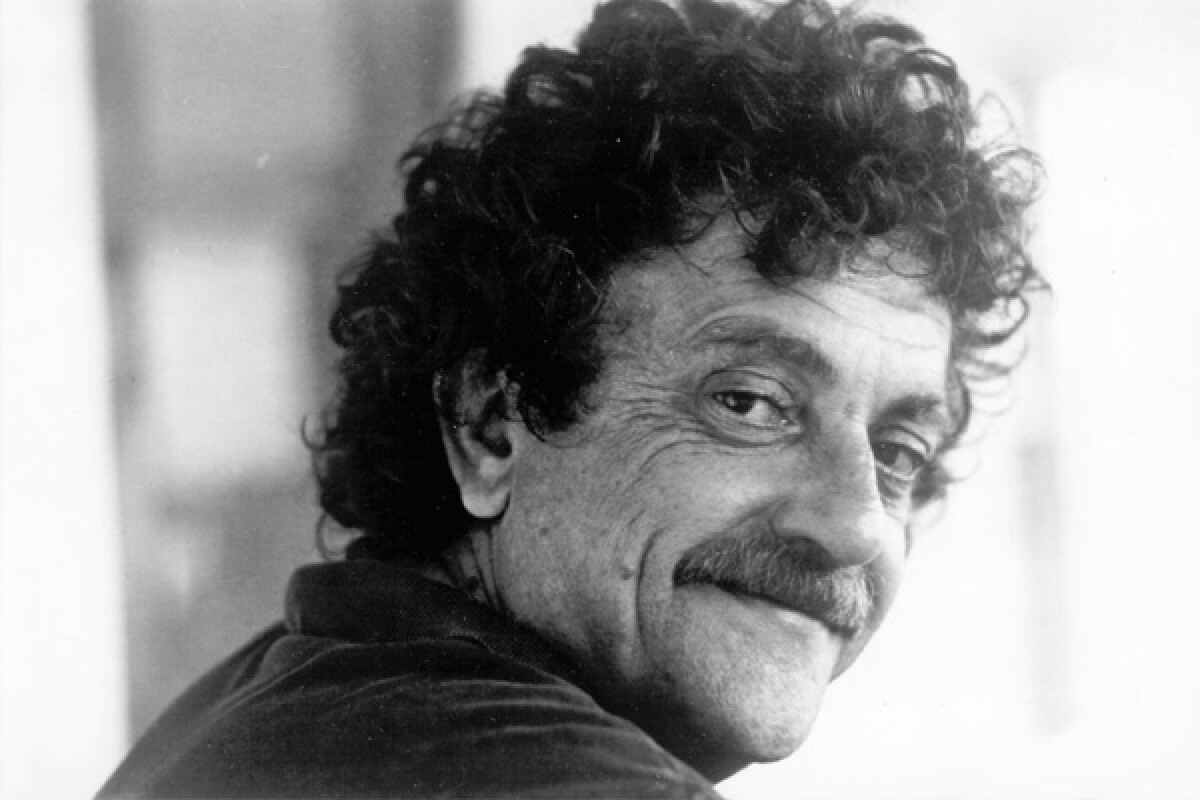

Vonnegut Kurt

Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. (November 11, 1922 – April 11, 2007) was an American writer. His works, such as Cat's Cradle (1963), Slaughterhouse-Five (1969), and Breakfast of Champions (1973), blend satire, gallows humor, and science fiction. As a citizen, he was a lifelong supporter of the American Civil Liberties Union and a pacifist intellectual, who often was critical of the society that he lived in. He was known for his humanist beliefs and was honorary president of the American Humanist Association.

The New York Times headline at the time of his death called him "the counterculture's novelist."

Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., was born in Indianapolis, Indiana, to third-generation German-American parents, Edith (Lieber) Vonnegut and Kurt Vonnegut, Sr.. Both his father and his grandfather Bernard Vonnegut attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and were architects in the Indianapolis firm of Vonnegut & Bohn. His great-grandfather, Clemens Vonnegut, Sr., was the founder of the Vonnegut Hardware Company, an Indianapolis firm. Vonnegut had an older brother, Bernard and a sister, Alice. Bernard, later an atmospheric scientist at the University at Albany, discovered that silver iodide could be used for cloud seeding, the process of artificially stimulating precipitation.

Vonnegut graduated from Shortridge High School in Indianapolis in May 1940 and went to Cornell University later that year. He majored in chemistry, and was assistant managing editor and associate editor of The Cornell Daily Sun. He was a member of the Delta Upsilon Fraternity, as was his father.

Vonnegut while in the army, early 1940s

While at Cornell, Vonnegut enlisted in the United States Army during World War II. The Army transferred him to the Carnegie Institute of Technology, and later to the University of Tennessee to study mechanical engineering. On Mother's Day 1944, while he was visiting his parents during a three day trip, he woke up to find that his mother had committed suicide with sleeping pills.

His experience as a soldier and prisoner of war had a profound influence on his later work. Reassigned to a combat unit due to the manpower needs of the Allied invasion of France, Vonnegut was captured while a private with the 423rd Infantry Regiment, 106th Infantry Division during the Battle of the Bulge. On December 19, 1944, the 106th Division was cut off from the rest of Courtney Hodges's First Army. "The other American divisions on our flanks managed to pull out; we were obliged to stay and fight. Bayonets aren't much good against tanks." Imprisoned in Dresden, he was chosen as a leader of the prisoners of war because he spoke some German. After telling some German guards "what [he] was going to do to them when the Russians came," he was beaten and had his position as leader revoked. He witnessed the Allied firebombing of Dresden in February 1945, which destroyed most of the historic city.

Vonnegut was part of a group of American prisoners of war who survived the bombing in an underground slaughterhouse meat locker used as an ad hoc detention facility. The German guards called the building Schlachthof Fünf ("Slaughterhouse Five"), and the POWs adopted that name. Vonnegut said that the aftermath of the attack on the defenseless city was "utter destruction" and "carnage unfathomable." The experience was the inspiration for his famous novel, Slaughterhouse-Five, and is a central theme in at least six of his other books. In Slaughterhouse-Five—which is nominally a fictional work—he described the ruined city as resembling the surface of the moon. He said the German guards put the surviving POWs to work, breaking into basements and bomb shelters to gather bodies for mass burial, while German civilians cursed and threw rocks at them. Vonnegut remarked, "There were too many corpses to bury. So instead the Germans sent in troops with flamethrowers. All these civilians' remains were burned to ashes."

Vonnegut was liberated by Red Army soldiers in May 1945 at the Saxony-Czechoslovakian border. He returned to the US and was awarded a Purple Heart on May 22, 1945 for what he called a "ludicrously negligible wound." Later, writing facetiously in Timequake, he said that he was given the decoration after suffering a case of "frostbite." His other decorations included the Army Good Conduct Medal, the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal (which is shown mounted with three bronze service stars in the Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library), the Prisoner of War Medal, the World War II Victory Medal and the Combat Infantryman Badge. Vonnegut was discharged with the rank of Corporal.

After the war, Vonnegut attended the University of Chicago as a graduate student in anthropology; he also worked at the City News Bureau of Chicago. He described his work there: "Well, the Chicago City News Bureau was a tripwire for all the newspapers in town when I was there, and there were five papers, I think. We were out all the time around the clock and every time we came across a really juicy murder or scandal or whatever, they'd send the big time reporters and photographers, otherwise they'd run our stories. So that's what I was doing, and I was going to university at the same time". Vonnegut admitted that he was a poor anthropology student, with one professor remarking that some of the students were going to be professional anthropologists, but he was not one of them. According to Vonnegut in Bagombo Snuff Box, the university rejected his first thesis on the necessity of accounting for the similarities between Cubist painters and the leaders of late nineteenth century Native American uprisings, saying it was "unprofessional".

In 1947 Vonnegut left Chicago to work in Schenectady, New York, in public relations for General Electric, where his brother Bernard worked in the research department. Vonnegut was a technical writer, but he was also known for writing well past his typical work hours. While in Schenectady, Vonnegut lived in the tiny hamlet of Alplaus, located within the town of Glenville, just across the Mohawk River from Schenectady. Vonnegut rented an upstairs apartment located along Alplaus Creek across the street from the Alplaus Volunteer Fire Department, where he was an active volunteer firefighter for a few years. To this day, the apartment where Vonnegut lived for a brief time still has a desk at which he wrote many of his short stories. Vonnegut carved his name on its underside.

In the mid-1950s, Vonnegut worked very briefly for Sports Illustrated magazine, where he was assigned to write a piece on a racehorse who had jumped a fence and attempted to run away. After staring at the blank piece of paper on his typewriter all morning, he typed, "The horse jumped over the fucking fence" and left. On the verge of abandoning writing, Vonnegut was offered a teaching job at the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop. While he was there in the early 1960s, his novel Cat's Cradle became a bestseller, and he began Slaughterhouse-Five. The latter novel is considered one of the best American novels of the twentieth century, appearing on the 100 best lists of Time magazine, and the Modern Library.

Early in his adult life he moved to Barnstable, Massachusetts, a town on Cape Cod where, in 1957, he established one of the first Saab dealerships in the US. The business failed within a year.

The author's name appears in print as "Kurt Vonnegut, Jr." throughout the first half of his published writing career; beginning with the 1976 publication of Slapstick, he dropped the "Jr." and was billed simply as Kurt Vonnegut.

After returning from World War II, Kurt Vonnegut married his childhood sweetheart, Jane Marie Cox, writing about their courtship in several of his short stories. In the 1960s they lived in Barnstable, Massachusetts, where for a while Vonnegut worked at his Saab dealership. The couple separated in 1970. That same year, Vonnegut began living with the woman who later would become his second wife, photographer Jill Krementz. He did not divorce Cox until 1979. Krementz and Vonnegut were married after the divorce from Cox was finalized.

He raised seven children: three from his first marriage; three of his sister Alice's four children, adopted by Vonnegut after her death from cancer; and a seventh, Lily, adopted with Krementz. His son, Mark Vonnegut, a pediatrician, has written two books: one about his experiences in the late 1960s and his major psychotic breakdown and recovery; the other includes anecdotes of growing up when his father was a struggling writer, his subsequent illness and a more recent breakdown in 1985, as well as what life has been like since then. Mark was named after Mark Twain, whom Vonnegut considered an American saint.

His daughter Edith ("Edie"), an artist, was named after Kurt Vonnegut's mother, Edith Lieber. She has had her work published in a book entitled Domestic Goddesses and was once married to Geraldo Rivera.

His youngest biological daughter, Nanette ("Nanny"), was named after Nanette Schnull, Vonnegut's paternal grandmother. She is married to realist painter Scott Prior and is the subject of several of his paintings, notably "Nanny and Rose".

Of Vonnegut's four adopted children, three are his nephews: James, Steven, and Kurt Adams. The fourth is Lily, a girl he adopted as an infant in 1982. James, Steven, and Kurt were adopted after a traumatic week in 1958, during which their father James Carmalt Adams was killed in the Newark Bay rail crash on September 15, when his commuter train went off the open Newark Bay bridge in New Jersey, and their mother—Kurt's sister Alice—died of cancer. In Slapstick, Vonnegut recounts that Alice's husband died two days before Alice did. Her family had tried to hide the knowledge from her, but she found out when an ambulatory patient gave her a copy of the New York Daily News a day before she died. The fourth and youngest of his sister's boys, Peter Nice, was an infant and went to live with a first cousin of their father in Birmingham, Alabama.

Adopted as an infant while Vonnegut was married to Jill Krementz, his daughter, Lily, became a singer, actress, and the producer of the YouTube series, "The Most Popular Girls in School".

Vonnegut's first wife Jane Marie Cox later married Adam Yarmolinsky and she wrote an account of the Vonneguts' life with the Adams children. It was published after her death as the book, Angels Without Wings: A Courageous Family's Triumph Over Tragedy.

On November 11, 1999, an asteroid was named in Vonnegut's honor: 25399 Vonnegut.

A lifelong smoker, Vonnegut smoked unfiltered Pall Mall cigarettes, a habit he sardonically referred to as a "classy way to commit suicide".

Vonnegut taught at Harvard University, where he was a lecturer in English, and the City College of New York, where he was a distinguished professor.

Vonnegut died at the age of 84 on April 11, 2007, from head injuries suffered while falling down a flight of stairs in his home

Vonnegut's first published short story, "Report on the Barnhouse Effect", appeared in the February 11, 1950, edition of Collier's (it has since been reprinted in his short story collection, Welcome to the Monkey House). His first novel was the dystopian work Player Piano (1952), in which human workers have been largely replaced by machines. He continued to write short stories before his second novel, The Sirens of Titan, was published in 1959.

Through the 1960s, the form of his work changed, from the relatively orthodox structure of Cat's Cradle to the acclaimed, semi-autobiographical Slaughterhouse-Five, given a more experimental structure by using time travel as a plot device. These structural experiments were continued in Breakfast of Champions (1973), which includes many rough illustrations, lengthy non-sequiturs, and an appearance by the author as a deus ex machina.

Breakfast of Champions became one of his best-selling novels. It includes, in addition to the author, several of Vonnegut's recurring characters. One of them, science fiction author Kilgore Trout, plays a major role and interacts with the author's character.

In 1974, Venus on the Half-Shell, a book by Philip José Farmer written in a style similar to that of Vonnegut, was attributed to Kilgore Trout. This caused some confusion among readers, as for some time many assumed that Vonnegut wrote it. When the truth of its authorship was revealed, Vonnegut was reportedly "not amused". In an issue of The Alien Critic/Science Fiction Review, published by Richard E. Geis, Farmer claimed to have received a very angry telephone call from Vonnegut about it.

Although many of his novels involved science fiction themes, they were read widely and reviewed outside the field, due in no small part to their anti-authoritarianism. For example, in his seminal short story, "Harrison Bergeron", egalitarianism is rigidly enforced by overbearing state authority, engendering horrific repression. In much of his work, Vonnegut's own voice is apparent, often filtered through his character, the science fiction author Kilgore Trout (whose name is based on that of real-life science fiction writer Theodore Sturgeon). His works are characterized by wild leaps of imagination and a deep cynicism, tempered by humanism. In the foreword to Breakfast of Champions, Vonnegut wrote that as a child, he saw men with locomotor ataxia, and it struck him that these men walked as if they were broken machines; it followed that healthy people were working machines, suggesting that humans are helpless prisoners of determinism. Vonnegut also explored this theme in Slaughterhouse-Five, in which protagonist Billy Pilgrim "has come unstuck in time" and has so little control over his own life that he cannot even predict which part of it he will be living through from minute to minute.

Vonnegut's well-known phrase "so it goes", used ironically in reference to death, also originated in Slaughterhouse-Five. "Its combination of simplicity, irony, and rue is very much in the Vonnegut vein".

With the publication of his novel Timequake in 1997, Vonnegut announced his retirement from writing fiction. He was in his seventies. He continued to write for the magazine In These Times, where he was a senior editor, until his death in 2007. In that work he focused on subjects ranging from contemporary U.S. politics to simple observational pieces on topics such as a trip to the post office. In 2005, many of his essays were collected in A Man Without a Country, which he insisted would be his last contribution to letters.

An August 2006 article reported:

He has stalled finishing his highly anticipated novel If God Were Alive Today —or so he claims. "I've given up on it... It won't happen... The Army kept me on because I could type, so I was typing other people's discharges and stuff. And my feeling was, 'Please, I've done everything I was supposed to do. Can I go home now?' That's what I feel right now. I've written books. Lots of them. Please, I've done everything I'm supposed to do. Can I go home now?"

Vonnegut died the following year, on April 11, 2007, at the age of eighty-four.

The April 2008 issue of Playboy featured the first published excerpt from Armageddon in Retrospect, the initial posthumous collection of Vonnegut's work. The book was published in the same month. It included previously unpublished short stories and a letter that was written to his family during World War II when Vonnegut was a prisoner of war. The book also contains drawings by Vonnegut and a speech he wrote shortly before his death. Its introduction was written by his son, Mark Vonnegut. The second posthumous collection Look at the Birdie was published in 2009.

Vonnegut's work as a graphic artist began with his illustrations for Slaughterhouse-Five and developed with Breakfast of Champions, which included numerous felt-tip pen illustrations. Many Vonnegut works of art may be found in his novels and short story collections, such as Armageddon in Retrospect. Later in his career, he became more interested in art, particularly silk-screen prints, which he pursued in collaboration with Joe Petro III. Vonnegut cited artists Paul Klee and Georges Braque as particular influences. According to his daughter Nanette, Vonnegut also was influenced by illustrators, Al Hirschfeld and Edward Gorey.

In October 1980, Vonnegut exhibited his drawings in pen, pencil, and colored felt-tipped markers at the Margo Feiden Galleries Ltd. in New York. Fellow writers Norman Mailer and George Plimpton attended the opening of the Vonnegut exhibition, as did television personality and fellow artist, Morley Safer. Later, Vonnegut would remark, "I actually had a one-person show of drawings a few years back... in Greenwich Village, not because my pictures were any good but because people had heard of me". On the occasion of the show's opening, Vonnegut expressed his preference for using colored felt-tipped markers rather than oil paints or watercolor. "Oil is such a commitment", Vonnegut explained, whereas he found watercolors "too bland, too weak". He said, however, "they make such extraordinary Magic Markers, such brilliant colors. It makes things very easy". He also compared the creative process of drawing with that involved in writing. "If you make a mistake on a picture it's satisfying to wad it up and toss it out" he said. "When you have to do that with a written page, it's a more depressing failure." Whereas the writer is only satisfied upon the work's completion, Vonnegut said, "the act [of painting] itself is enjoyable". He further explained that "in a picture there may be 10 or 12 significant details. On a printed page there are 2,500". As to his art's significance, Vonnegut declared, "My drawings are as rare as exotic postage stamps."

In 2004, Vonnegut participated in the project The Greatest Album Covers That Never Were, for which he created an album cover for Phish called Hook, Line and Sinker, which has been included in a traveling exhibition for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

May 2014, Vonnegut's daughter, Nanette Vonnegut, published a book of her father's drawings entitled Kurt Vonnegut Drawings through Monacelli Press, a division of Random House. In her introduction, Nanette discusses her father's preference for drawing to writing. She quotes him that "the making of pictures is to writing what laughing gas is to the Asian influenza." A book signing and an exhibition of original drawings by Vonnegut was held at the Margo Feiden Galleries Ltd. in New York, the gallery where, in 1980, Vonnegut had shown his work. Attendees at the event continued the original guestbook from Vonnegut's 1980 solo show. The Wall Street Journal reported that, "if they flipped back a few pages, they could see the signatures of luminaries like George Plimpton, some of which were accompanied by personal messages to Mr. Vonnegut." Margo Feiden related to the Journal that "she was struck by Mr. Vonnegut after he told her that he thought of himself as a visual artist but had to work as an author to make a living."

Share: