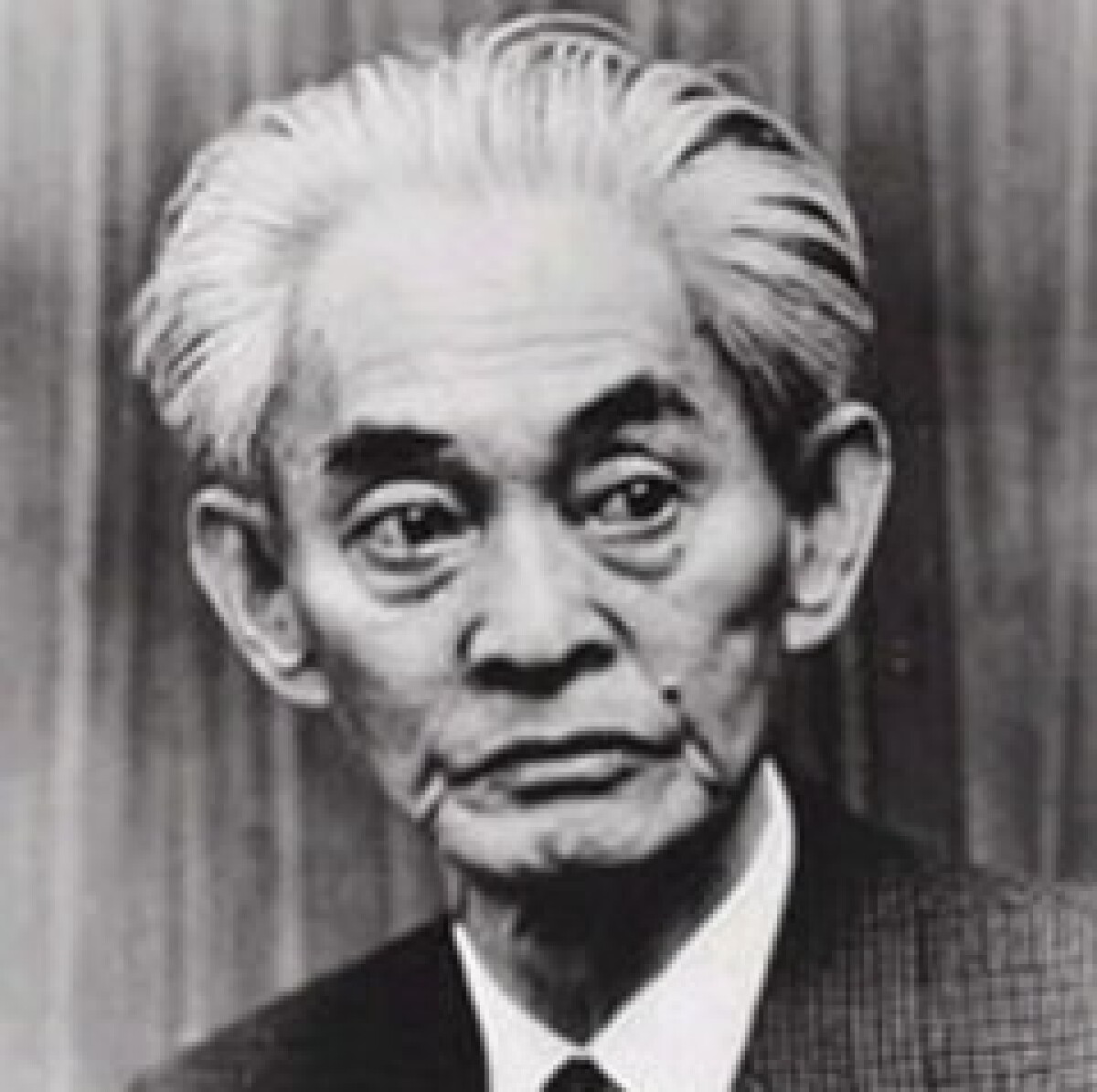

Kawabata Yasunari

Yasunari Kawabata (11 June 1899 – 16 April 1972) was a Japanese novelist and short story writer whose sparse, lyrical, subtly-shaded prose works won him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1968, the first Japanese author to receive the award. His works have enjoyed broad international appeal and are still widely read.

Born in Osaka, Japan, into a well-established doctor's family, Yasunari was orphaned when he was four, after which he lived with his grandparents. He had an older sister who was taken in by an aunt, and whom he met only once thereafter, at the age of ten (July 1909) (she died when he was 11). Kawabata's grandmother died when he was seven (September 1906), and his grandfather when he was fifteen (May 1914).

Having lost all close relatives, he moved in with his mother's family (the Kurodas). However, in January 1916, he moved into a boarding house near the junior high school (comparable to a modern high school) to which he had formerly commuted by train. Through many of Kawabata’s works the sense of distance in his life is represented. He often gives the impression that his characters have built up a wall around them that moves them into isolation. In a 1934 published work Kawabata wrote: “I feel as though I have never held a woman’s hand in a romantic sense[…] Am I a happy man deserving of pity?”. Indeed this does not have to be taken literally, but it does show the type of emotional insecurity that Kawabata felt, especially experiencing two painful love affairs at a young age. One of those painful love episodes was with Hatsuyo Ito (1906-1951) whom he met when he was 20 years old. His unsent love letter to her was recently found at his former residence in Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture.

After graduating from junior high school in March 1917, just before his 18th birthday, he moved to Tokyo, hoping to pass the exams of Dai-ichi Kōtō-gakkō (First Upper School), which was under the direction of the Tokyo Imperial University. He succeeded in the exam the same year and entered the Humanities Faculty as an English major (July 1920).

Kawabata graduated in 1924, by which time he had already caught the attention of Kikuchi Kan and other noted writers and editors through his submissions to Kikuchi's literary magazine, the Bungei Shunju.

In addition to fiction writing, Kawabata also worked as a reporter, most notably for the Mainichi Shimbun. Although he refused to participate in the militaristic fervor that accompanied World War II, he also demonstrated little interest in postwar political reforms. Along with the death of all his family while he was young, Kawabata suggested that the War was one of the greatest influences on his work, stating he would be able to write only elegies in postwar Japan. Still, many commentators detect little thematic change between Kawabata's prewar and postwar writings.

Kawabata apparently committed suicide in 1972 by gassing himself, but a number of close associates, including his widow, consider his death to have been accidental. One thesis, as advanced by Donald Richie, was that he mistakenly unplugged the gas tap while preparing a bath. Many theories have been advanced as to his potential reasons for killing himself, among them poor health (the discovery that he had Parkinson's disease), a possible illicit love affair, or the shock caused by the suicide of his friend Yukio Mishima in 1970. Unlike Mishima, Kawabata left no note, and since (again unlike Mishima) he had not discussed significantly in his writings the topic of taking his own life, his motives remain unclear. However, his Japanese biographer, Takeo Okuno, has related how he had nightmares about Mishima for two or three hundred nights in a row, and was incessantly haunted by the specter of Mishima. In a persistently depressed state of mind, he would tell friends during his last years that sometimes, when on a journey, he hoped his plane would crash.

While still a university student, Kawabata re-established the Tokyo University literary magazine Shin-shichō ("New Tide of Thought"), which had been defunct for more than four years. There he published his first short story, "Shokonsai ikkei" ("A View from Yasukuni Festival") in 1921. During university, he changed faculties to Japanese literature and wrote a graduation thesis titled, "A short history of Japanese novels". He graduated from university in March 1924.

In October 1924, Kawabata, Kataoka Teppei, Yokomitsu Riichi, and a number of other young writers started a new literary journal Bungei Jidai ("The Artistic Age"). This journal was a reaction to the entrenched old school of Japanese literature, specifically the Japanese movement descended from Naturalism, while it also stood in opposition to the "workers'" or proletarian literature movement of the Socialist/Communist schools. It was an "art for art's sake" movement, influenced by European Cubism, Expressionism, Dada, and other modernist styles. The term Shinkankakuha, which Kawabata and Yokomitsu used to describe their philosophy, has often been mistakenly translated into English as "Neo-Impressionism". However, Shinkankakuha was not meant to be an updated or restored version of Impressionism; it focused on offering "new impressions" or, more accurately, "new sensations" or "new perceptions" in the writing of literature. An early example from this period is the draft of Hoshi wo nusunda chichi (The Father who stole a Star), an adaption of Ferenc Molnár's play Liliom.

Kawabata started to achieve recognition with a number of short stories shortly after he graduated, receiving acclaim for "The Dancing Girl of Izu" in 1926, a story about a melancholy student who, on a walking trip down Izu Peninsula, meets a young dancer, and returns to Tokyo in much improved spirits. This story, which explored the dawning eroticism of young love, was successful because he used dashes of melancholy and even bitterness to offset what might have otherwise been overly sweet. Most of his subsequent works explored similar themes.

In the 1920s, Kawabata was living in the plebeian district of Asakusa, Tokyo. During this period, Kawabata experimented with different styles of writing. In Asakusa kurenaidan (The Scarlet Gang of Asakusa), serialized from 1929 to 1930, he explores the lives of the demimonde and others on the fringe of society, in a style echoing that of late Edo period literature. On the other hand, his Suisho genso (Crystalline Fantasy) is pure stream-of-consciousness writing. He was even involved in writing the script for the experimental film A Page of Madness.

Kawabata relocated from Asakusa to Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture, in 1934 and, although he initially enjoyed a very active social life among the many other writers and literary people residing in that city during the war years and immediately thereafter, in his later years he became very reclusive.

One of his most famous novels was Snow Country, started in 1934 and first published in installments from 1935 through 1947. Snow Country is a stark tale of a love affair between a Tokyo dilettante and a provincial geisha, which takes place in a remote hot-spring town somewhere in the mountainous regions of northern Japan. It established Kawabata as one of Japan's foremost authors and became an instant classic, described by Edward G. Seidensticker as "perhaps Kawabata's masterpiece".

After the end of World War II, Kawabata's success continued with novels such as Thousand Cranes (a story of ill-fated love); The Sound of the Mountain; The House of the Sleeping Beauties; Beauty and Sadness; and The Old Capital .

His two most important post-war works are Sembazuru (Thousand Cranes) from 1949 to 1951, and Yama no Oto (The Sound of the Mountain), 1949–1954. Sembazuru is centered on the tea ceremony and hopeless love. The protagonist is attracted to the mistress of his dead father and, after her death, to her daughter, who flees from him. The tea ceremony provides a beautiful background for ugly human affairs, but Kawabata’s intent is rather to explore feelings about death. The tea ceremony utensils are permanent and forever, whereas people are frail and fleeting. These themes of implicit incest, impossible love and impending death are again explored in Yama no Oto, set in Kawabata’s home town of Kamakura. The protagonist, an aging man, has grown disappointed of his children and has lost all passion for his wife. He is strongly attracted to someone forbidden — his daughter in law — and his thoughts for her are interspersed with memories of another forbidden love, for his dead sister-in-law.

The book that he himself considered his finest work, The Master of Go (1951), is in severe contrast to his other works. It is a semi-fictional recounting of a major Go match in 1938, on which Kawabata had actually reported for the Mainichi newspaper chain. It was the last game of the master Shūsai's career and he lost to his younger challenger, only to die a little over a year later. Although the novel is moving on the surface as a retelling of a climactic struggle, some readers consider it a symbolic parallel to the defeat of Japan in World War II.

Kawabata left many of his stories apparently unfinished, sometimes to the annoyance of readers and reviewers, but this goes hand to hand with his aesthetics of art for art's sake, leaving outside any sentimentalism, or morality, that an ending would give to any book. This was done intentionally, as Kawabata felt that vignettes of incidents along the way were far more important than conclusions. He equated his form of writing with the traditional poetry of Japan, the haiku.

As the president of Japanese P.E.N. for many years after the war (1948–1965), Kawabata was a driving force behind the translation of Japanese literature into English and other Western languages. He was appointed an Officer of the Order of Arts and Letters of France in 1960, and awarded Japan's Order of Culture the following year.

As detailed in the next section, in 1968 Kawabata became the first Japanese to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Yasunari Kawabata was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature on October 16, 1968, the first Japanese person to receive such a distinction. In awarding the prize "for his narrative mastery, which with great sensibility expresses the essence of the Japanese mind", the Nobel Committee cited three of his novels, Snow Country, Thousand Cranes, and The Old Capital.

Kawabata's Nobel Lecture was titled "Japan, The Beautiful and Myself". Zen Buddhism was a key focal point of the speech; much was devoted to practitioners and the general practices of Zen Buddhism and how it differed from other types of Buddhism. He presented a severe picture of Zen Buddhism, where disciples can enter salvation only through their efforts, where they are isolated for several hours at a time, and how from this isolation there can come beauty. He noted that Zen practices focus on simplicity and it is this simplicity that proves to be the beauty. "The heart of the ink painting is in space, abbreviation, what is left undrawn." From painting he moved on to talk about ikebana and bonsai as art forms that emphasize the simplicity and the beauty that arises from the simplicity. "The Japanese garden, too, of course symbolizes the vastness of nature."

In addition to the numerous mentions of Zen and nature, one point that was briefly mentioned in Kawabata’s lecture was that of suicide. Kawabata reminisced of other famous Japanese authors who committed suicide, in particular Ryūnosuke Akutagawa. He contradicted the custom of suicide as being a form of enlightenment, mentioning the priest Ikkyu, who also thought of suicide twice. He quoted Ikkyu, "Among those who give thoughts to things, is there one who does not think of suicide?" There was much speculation about this quote being a clue to Kawabata's suicide in 1972, two years after Mishima had committed suicide.

Share: