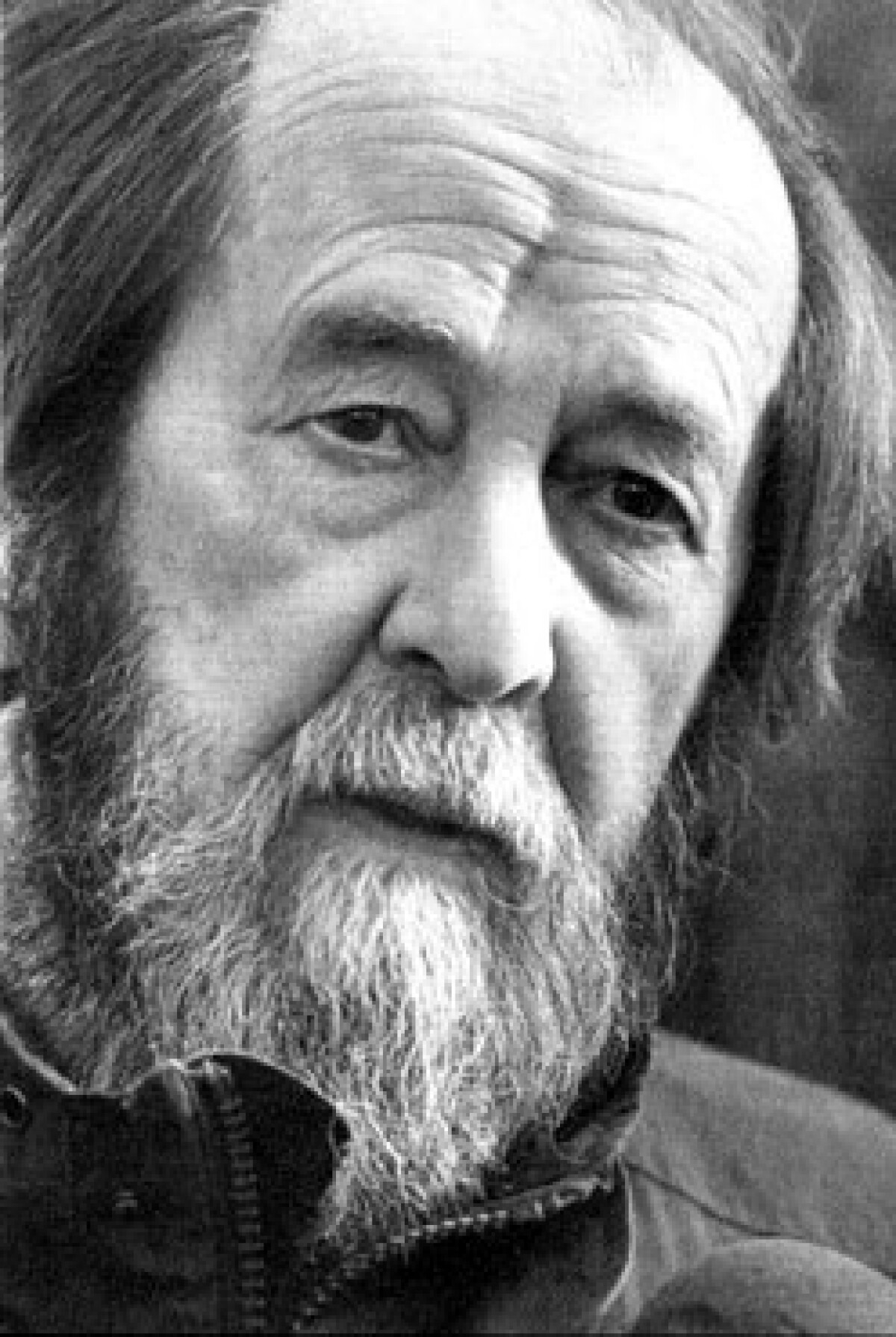

Solzhenitsyn Aleksandr

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn, (born Dec. 11, 1918, Kislovodsk, Russia—died Aug. 3, 2008, Troitse-Lykovo, near Moscow), Russian novelist and historian, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1970.

Solzhenitsyn was born into a family of Cossack intellectuals and brought up primarily by his mother (his father was killed in an accident before his birth). He attended the University of Rostov-na-Donu, graduating in mathematics, and took correspondence courses in literature at Moscow State University. He fought in World War II, achieving the rank of captain of artillery; in 1945, however, he was arrested for writing a letter in which he criticized Joseph Stalin and spent eight years in prisons and labour camps, after which he spent three more years in enforced exile. Rehabilitated in 1956, he was allowed to settle in Ryazan, in central Russia, where he became a mathematics teacher and began to write.

Encouraged by the loosening of government restraints on cultural life that was a hallmark of the de-Stalinizing policies of the early 1960s, Solzhenitsyn submitted his short novel Odin den iz zhizni Ivana Denisovicha (1962; One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich) to the leading Soviet literary periodical Novy Mir (“New World”). The novel quickly appeared in that journal’s pages and met with immediate popularity, Solzhenitsyn becoming an instant celebrity. Ivan Denisovich, based on Solzhenitsyn’s own experiences, described a typical day in the life of an inmate of a forced-labour camp during the Stalin era. The impression made on the public by the book’s simple, direct language and by the obvious authority with which it treated the daily struggles and material hardships of camp life was magnified by its being one of the first Soviet literary works of the post-Stalin era to directly describe such a life. The book produced a political sensation both abroad and in the Soviet Union, where it inspired a number of other writers to produce accounts of their imprisonment under Stalin’s regime.

Solzhenitsyn’s period of official favour proved to be short-lived, however. Ideological strictures on cultural activity in the Soviet Union tightened with Nikita Khrushchev’s fall from power in 1964, and Solzhenitsyn met first with increasing criticism and then with overt harassment from the authorities when he emerged as an eloquent opponent of repressive government policies. After the publication of a collection of his short stories in 1963, he was denied further official publication of his work, and he resorted to circulating them in the form of samizdat (“self-published”) literature—i.e., as illegal literature circulated clandestinely—as well as publishing them abroad.

The following years were marked by the foreign publication of several ambitious novels that secured Solzhenitsyn’s international literary reputation. V kruge pervom (1968; The First Circle) was indirectly based on his years spent working in a prison research institute as a mathematician. The book traces the varying responses of scientists at work on research for the secret police as they must decide whether to cooperate with the authorities and thus remain within the research prison or to refuse their services and be thrust back into the brutal conditions of the labour camps. Rakovy korpus (1968; Cancer Ward) was based on Solzhenitsyn’s hospitalization and successful treatment for terminally diagnosed cancer during his forced exile in Kazakhstan during the mid-1950s. The main character, like Solzhenitsyn himself, was a recently released inmate of the camps.

Share: