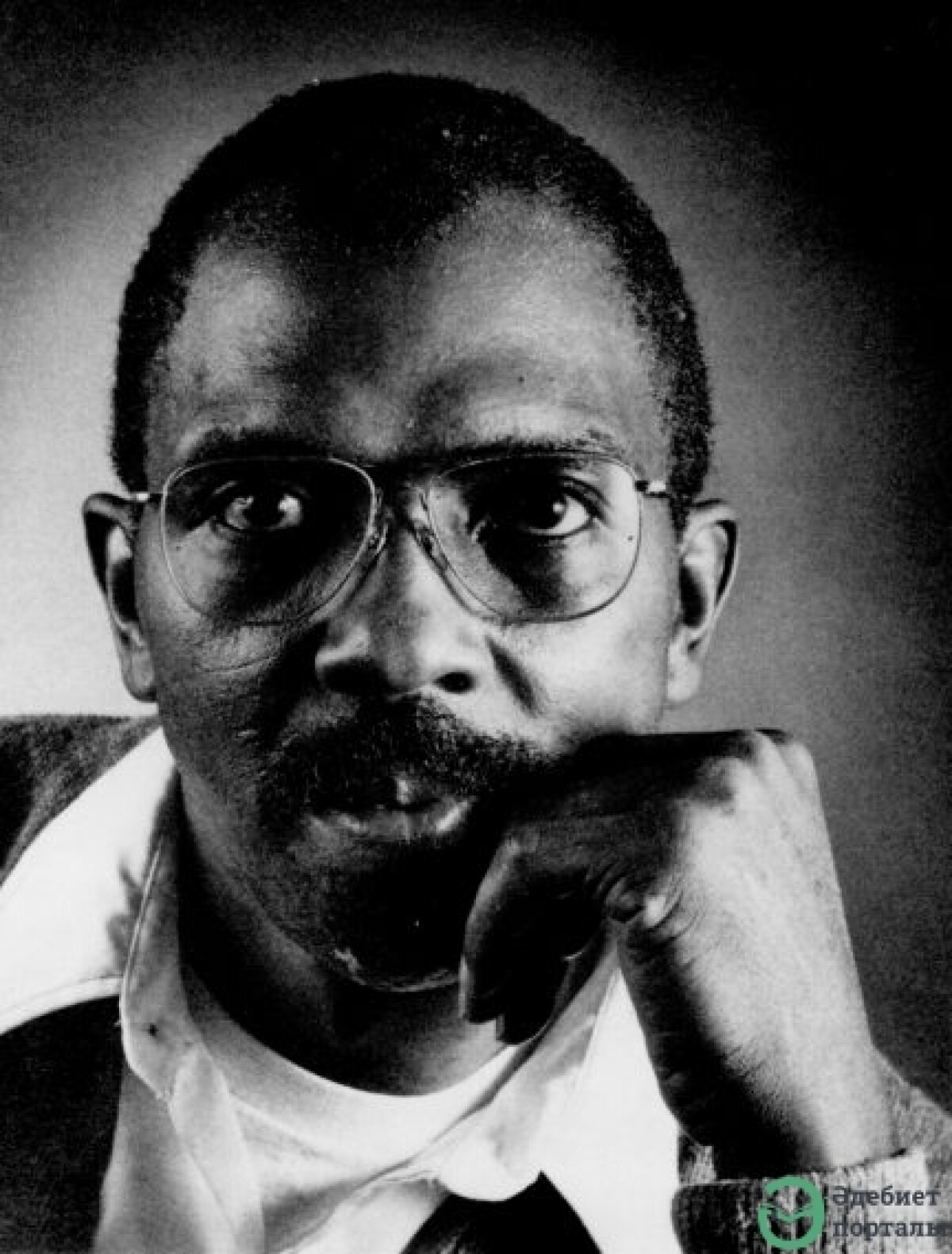

Etheridge Knight

Etheridge Knight was born in Corinth, Mississippi. He dropped out of high school while still a teenager and joined the army to serve in the Korea war. Wounded by shrapnel during the conflict, he returned to civilian life with an injury that led to drug addiction. Knight was convicted of robbery in 1960 and served eight years in the Indiana State Prison. According to Terrance Hayes, Knight’s “biography is a story of restless Americanness, African Americanness, and poetry. It has some Faulknerian family saga in it, some midcentury migration story, lots of masculine tragedy, lots of soul-of-the-artist lore.” While in prison, Knight began to write poetry, and he corresponded with, and received visits from, Black literary luminaries such as Dudley Randall and Gwendolyn Brooks. His first collection, Poems from Prison (1968) included the following text on its back cover: “I died in Korea from a shrapnel wound, and narcotics resurrected me. I died in 1960 from a prison sentence and poetry brought me back to life.” Knight’s work was immediately lauded as “another excellent example of the powerful truth of blackness in art,” wrote Shirley Lumpkin in the Dictionary of Literary Biography. “His work became important in Afro-American poetry and poetics and in the strain of Anglo-American poetry descended from Walt Whitman.”

Knight was married to poet Sonia Sanchez, and both were important members of the poets and artists connected to the Black Arts Movement. His work should be read in the context of that movement’s goals to inspire collective action and develop Black cultural identities distinct from dominant white power structures. As Craig Werner observes in Obsidian: Black Literature in Review: “Technically, Knight merges musical rhythms with traditional metrical devices, reflecting the assertion of an Afro-American cultural identity within a Euro-American context. Thematically, he denies that the figures of the singer… and the warrior… are or can be separate.” Knight went on to attain recognition as a major poet, earning both Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award nominations for Belly Song and Other Poems (1973). Knights honors and awards included fellowships and prizes from the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Poetry Society of America. In 1990 he earned a bachelor’s degree in American poetry and criminal justice from Martin Center University in Indianapolis.

When Knight entered prison, he was already an accomplished reciter of “toasts”—long, memorized, narrative poems, often in rhymed couplets, in which “sexual exploits, drug activities, and violent aggressive conflicts involving a cast of familiar folk… are related… using street slang, drug and other specialized argot, and often obscenities,” explains Lumpkin. Toast-reciting at Indiana State Prison not only refined Knight’s expertise in this traditional Black art form but also, according to Lumpkin, gave him a sense of identity and an understanding of the possibilities of poetry. “Since toast-telling brought him into genuine communion with others, he felt that poetry could simultaneously show him who he was and connect him with other people.” In an article for the Detroit Free Press about Dudley Randall, the founder of Broadside Press, Suzanne Dolezal, indicates that Randall was impressed with Knight and visited him frequently at the prison: “In a small room reserved for consultations with death row inmates, with iron doors slamming and prisoners shouting in the background, Randall convinced a hesitant Knight of his talent.” And, says Dolezal, Randall feels that because Knight was from the streets, “He may be a deeper poet than many of the others because he has felt more anguish.”

Much of Knight’s prison poetry, according to Patricia Liggins Hill in Black American Literature Forum focuses on imprisonment as a form of contemporary enslavement and looks for ways in which one can be free despite incarceration. Time and space are significant in the concept of imprisonment, and Hill indicates that “specifically, what Knight relies on for his prison poetry are various temporal/spatial elements which allow him to merge his personal consciousness with the consciousness of Black people.” Hill believes that this merging of consciousness “sets him apart from the other new Black poets… [who] see themselves as poets/ priests… Knight sees himself as being one with Black people.” Randall observes in Broadside Memories: Poets I Have Knownthat “Knight does not objure rime like many contemporary poets. He says the average Black man in the streets defines poetry as something that rimes, and Knight appeals to the folk by riming.” Randall notes that while Knight’s poetry is “influenced by the folk,” it is also “prized by other poets.”

Knight’s Born of a Woman: New and Selected Poems (1980) includes work from Poems from Prison, Black Voices from Prison (1970), a collection of prison poetry from Black inmates that Knight edited, and Belly Song and Other Poems. Reviewing Born of a Woman for Black American Literature Forum, Hill described Knight as a “masterful blues singer, a singer whose life has been ‘full of trouble’ and thus whose songs resound a variety of blues moods, feelings, and experiences and later take on the specific form of a blues musical composition.” Lumpkin suggested that an “awareness of the significance of form governed Knight’s arrangement of the poems in the volume as well as his revisions… He put them in clusters or groupings under titles which are musical variations on the book’s essential theme—life inside and outside prison.” Calling this structure a “jazz composition mode,” Lumpkin also notes that it was once used by Langston Hughes in an arrangement of his poetry.

In the Los Angeles Times Book Review Peter Clothier considered Knight’s poems to be “tools for self-discovery and discovery of the world - a loud announcement of the truths they pry loose.” And Knight himself once told CAhe believed a definition of art and aesthetics assumes that “every man is the master of his own destiny and comes to grips with the society by his own efforts. The ‘true’ artist is supposed to examine his own experience of this process as a reflection of his self, his ego.” Knight felt “white society denies art, because art unifies rather than separates; it brings people together instead of alienating them.” The western/European aesthetic dictates that “the artist speak only of the beautiful (himself and what he sees); his task is to edify the listener, to make him see beauty of the world.” Black artists must stay away from this because “the red of this aesthetic rose got its color from the blood of black slaves, exterminated Indians, napalmed Vietnamese children.” According to Knight, the black artist must “perceive and conceptualize the collective aspirations, the collective vision of black people, and through his art form give back to the people the truth that he has gotten from them. He must sing to them of their own deeds, and misdeeds.”

Etheridge Knight died in 1991.

Share: