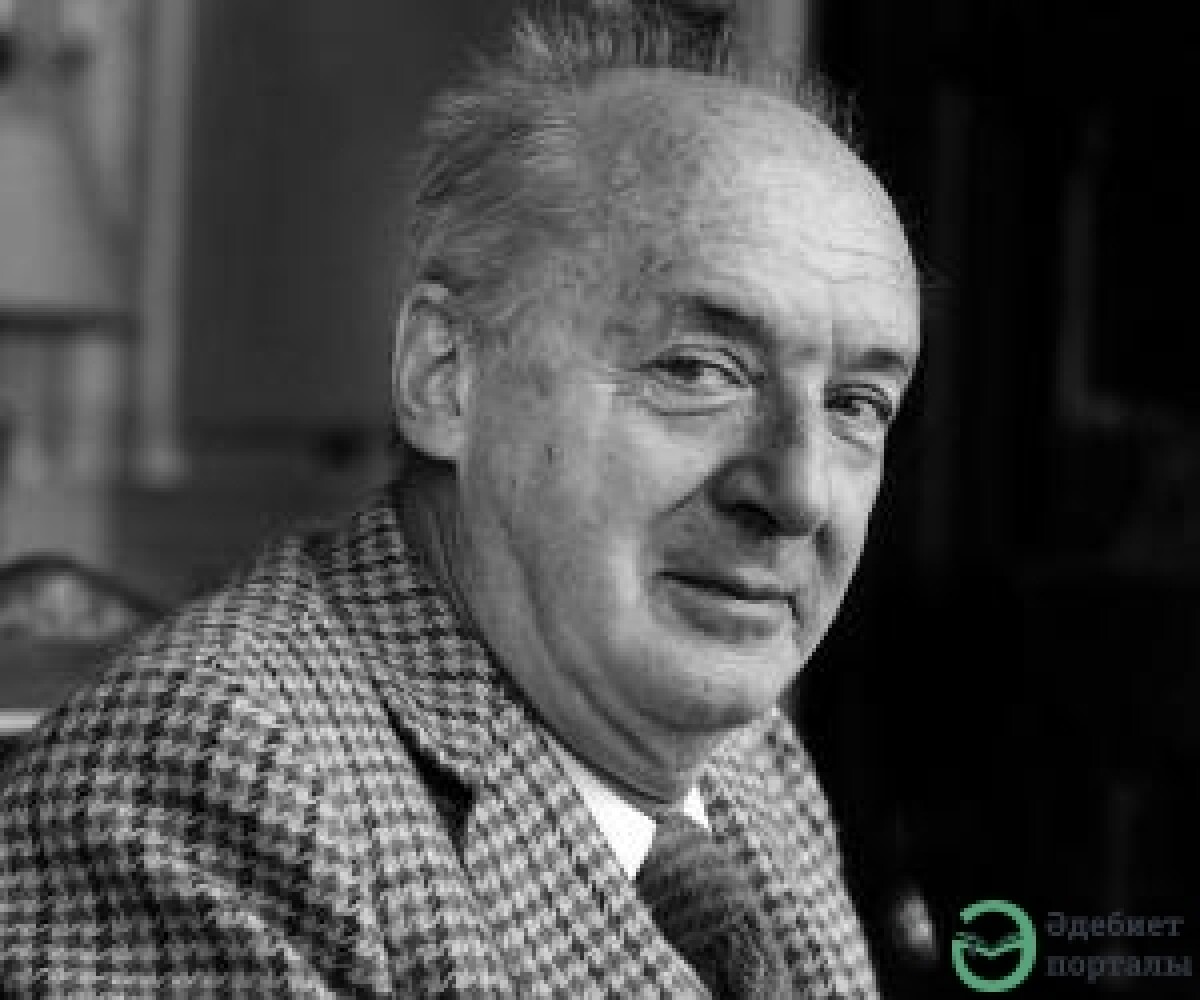

Vladimir Nabokov

Vladimir Nabokov was born into an old aristocratic family. His father, V.D. Nabokov, was a leader of the pre-Revolutionary liberal Constitutional Democratic Party (Kadets) in Russia and was the author of numerous books and articles on criminal law and politics, among them The Provisional Government (1922), which was one of the primary sources on the downfall of the Kerensky regime. In 1922, after the family had settled in Berlin, the elder Nabokov was assassinated by a reactionary rightist while shielding another man at a public meeting; although his novelist son disclaimed any influence of this event upon his art, the theme of assassination by mistake has figured prominently in Nabokov’s novels. Nabokov’s enormous affection for his father and for the milieu in which he was raised is evident in his autobiography Speak, Memory (revised version, 1967).

Nabokov published two collections of verse, Poems (1916) and Two Paths (1918), before leaving Russia in 1919. He and his family made their way to England, and he attended Trinity College, Cambridge, on a scholarship provided for the sons of prominent Russians in exile. While at Cambridge he first studied zoology, but soon switched to French and Russian literature; he graduated with first-class honours in 1922 and subsequently wrote that his almost effortless attainment of this degree was “one of the very few ‘utilitarian’ sins on my conscience.” While still in England he continued to write poetry, mainly in Russian but also in English, and two collections of his Russian poetry, The Cluster and The Empyrean Path, appeared in 1923. In Nabokov’s mature opinion, these poems were “polished and sterile.”

Between 1922 and 1940 Nabokov lived in Germany and France, and, while continuing to write poetry, he experimented with drama and even collaborated on several unproduced motion-picture scenarios. A five-act play written 1923–24, Tragediya gospodina Morna (The Tragedy of Mr. Morn), was published posthumously, first in 1997 in a Russian literary journal and then in 2008 as a stand-alone volume. By 1925 he settled upon prose as his main genre. His first short had already been published in Berlin in 1924. His first novel, Mashenka (Mary), appeared in 1926; it was avowedly autobiographical and contains descriptions of the young Nabokov’s first serious romance as well as of the Nabokov family estate, both of which are also described in Speak, Memory. Nabokov did not again draw so heavily upon his personal experience as he had in Mashenka until his episodic novel about an emigre professor of Russian in the United States, Pnin (1957), which is to some extent based on his experiences while teaching (1948–58) Russian and European literature at Cornell University, Ithaca, New York.

Nabokov’s major critical works are an irreverent book about Nikolay Gogol (1944) and a monumental four-volume translation of, and commentary on, Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin (1964). What he called the “present, final version” of the autobiographical Speak, Memory, concerning his European years, was published in 1967, after which he began work on a sequel, Speak On, Memory, concerning the American years.

As Nabokov’s reputation grew in the 1930s so did the ferocity of the attacks made upon him. His idiosyncratic, somewhat aloof style and unusual novelistic concerns were interpreted as snobbery by his detractors—although his best Russian critic, Vladislav Khodasevich, insisted that Nabokov’s aristocratic view was appropriate to his subject matters: problems of art masked by allegory.

Nabokov’s reputation varies greatly from country to country. Until 1986 he was not published in the Soviet Union, not only because he was a “White Russian emigre” (he became a U.S. citizen in 1945) but also because he practiced “literary snobbism.” Critics of strong social convictions in the West also generally hold him in low esteem. But within the intellectual emigre community in Paris and Berlin between 1919 and 1939, V. Sirin (the literary pseudonym used by Nabokov in those years) was credited with being “on a level with the most significant artists in contemporary European literature and occupying a place held by no one else in Russian literature.” His reputation after 1940, when he changed from Russian to English after emigrating to the United States, mounted steadily until the 1970s, when he was acclaimed by a leading literary critic as “king over that battered mass society called contemporary fiction.”

When Nabokov died in 1977, he left behind a stack of index cards filled with the text of what was to become his final novel, The Original of Laura. On his deathbed, he instructed his wife, Vera, to burn the unfinished work. She instead placed it in a Swiss bank vault, where it remained the object of much speculation for three decades. With Véra’s death in 1991, responsibility for the final work fell to the Nabokovs’ son, Dmitri. In 2008 he announced his decision to allow its publication. The Original of Laura, which the younger Nabokov referred to as “the most concentrated distillation” of his father’s creativity, was released in 2009. Though it proved to be in a highly incomplete state, the text was nevertheless marked by Nabokov’s celebrated facility with allusion and wordplay. The story revolves around an obese intellectual, Philip, and his young, wild wife, Flora, who is the seeming subject of a scandalous novel written by one of her former lovers. The work also offers a view of Nabokov’s final writings on the theme of mortality, as Philip courts his own end via an act of “auto-dissolution,” a kind of willed erasure.

A collection of Nabokov’s missives to his wife was published as Letters to Vera (2015).

Share: