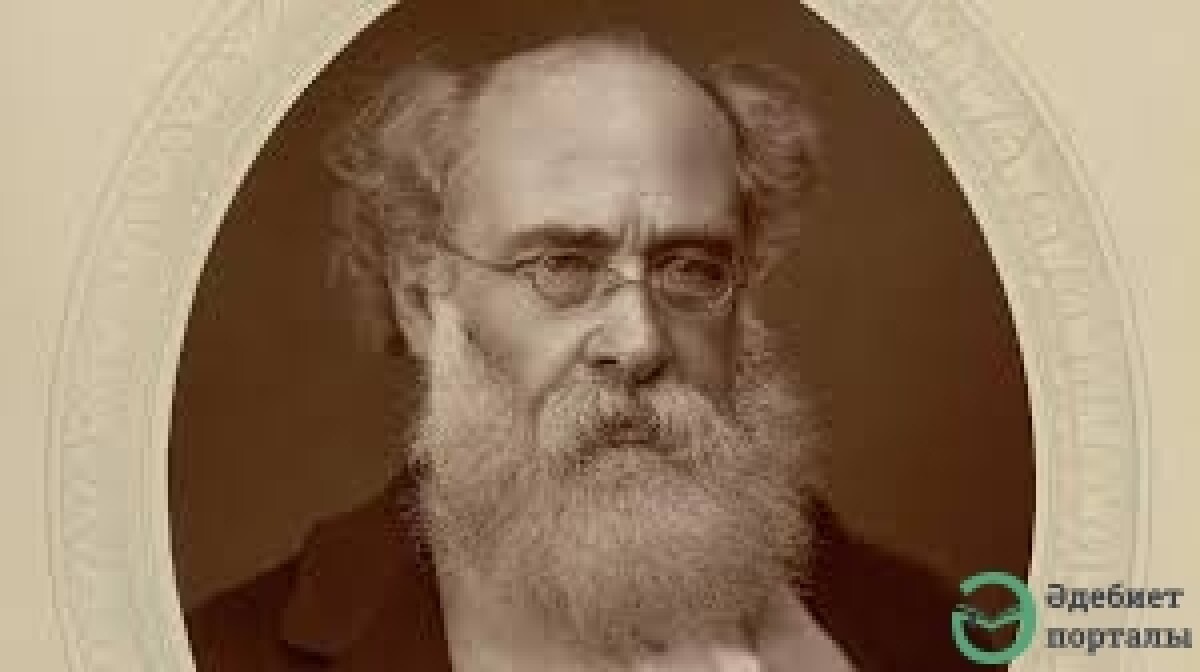

Anthony Trollope

Anthony Trollope, (born April 24, 1815, London, Eng.—died Dec. 6, 1882, London), English novelist whose popular success concealed until long after his death the nature and extent of his literary merit. A series of books set in the imaginary English county of Barsetshire remains his best loved and most famous work, but he also wrote convincing novels of political life as well as studies that show great psychological penetration. One of his greatest strengths was a steady, consistent vision of the social structures of Victorian England, which he re-created in his books with unusual solidity.

Trollope grew up as the son of a sometime scholar, barrister, and failed gentleman farmer. He was unhappy at the great public schools of Winchester and Harrow. Adolescent awkwardness continued until well into his 20s. The years 1834–41 he spent miserably as a junior clerk in the General Post Office, but he was then transferred as a postal surveyor to Ireland, where he began to enjoy a social life. In 1844 he married Rose Heseltine, an Englishwoman, and set up house at Clonmel, in Tipperary. He then embarked upon a literary career that leaves a dominant impression of immense energy and versatility.

The Warden (1855) was his first novel of distinction, a penetrating study of the warden of an old people’s home who is attacked for making too much profit from a charitable sinecure. During the next 12 years Trollope produced five other books set, like The Warden, in Barsetshire: Barchester Towers (1857), Doctor Thorne (1858), Framley Parsonage (1861), The Small House at Allington (1864), and The Last Chronicle of Barset (serially 1866–67; 1867). Barchester Towers is the funniest of the series; Doctor Thorne perhaps the best picture of a social system based on birth and the ownership of land; and The Last Chronicle, with its story of the sufferings of the scholarly Mr. Crawley, an underpaid curate of a poor parish, the most pathetic.

The Barsetshire novels excel in memorable characters, and they exude the atmosphere of the cathedral community and of the landed aristocracy.

In 1859 Trollope moved back to London, resigning from the civil service in 1867 and unsuccessfully standing as a Liberal parliamentary candidate in 1868. Before then, however, he had produced some 18 novels apart from the Barsetshire group. He wrote mainly before breakfast at a fixed rate of 1,000 words an hour. Outstanding among works of that period were Orley Farm (serially, 1861–62; 1862), which made use of the traditional plot of a disputed will, and Can You Forgive Her? (serially, 1864–65; 1865), the first of his political novels, which introduced Plantagenet Palliser, later duke of Omnium, whose saga was to stretch over many volumes down to The Duke’s Children (serially, 1879–80; 1880), a subtle study of the dangers and difficulties of marriage. In the political novels Trollope is less concerned with political ideas than with the practical working of the system—with the mechanics of power.

In about 1869 Trollope’s last, and in some respects most interesting, period as a writer began. Traces of his new style are to be found in the slow-moving He Knew He Was Right (serially, 1868–69; 1869), a subtle account of a rich man’s jealous obsession with his innocent wife. Purely psychological studies include Sir Harry Hotspur of Humblethwaite (serially, 1870; 1871) and Kept in the Dark (1882). Some of the later works, however, were sharply satirical: The Eustace Diamonds (serially, 1871–73; 1873), a study of the influence of money on sexual relationships; The Way We Live Now (serially, 1874–75; 1875), remarkable for its villain-hero, the financier Melmotte; and Mr. Scarborough’s Family (posthumously, 1883), which shows what can happen when the rights of property are wielded by a man of nihilistic temperament intent upon his legal rights.

Trollope’s final years were spent in the seclusion of a small Sussex village, where he worked on in the face of gradually diminishing popularity, failing health, and increasing melancholy. He was in London when he died, having been stricken there with paralysis.

Share: