The History and place of April Fools’ Day or All Fool’s Day or Day of laughter in Literature - a worldwide holiday, celebrated on April 1 in many countries. During this holiday it is customary to play friends and acquaintances, or just to make fun of them. Traditionally, in countries such as New Zealand, Ireland, Great Britain, Australia and South Africa, rallies are held only until noon, calling those who joke after this time "April Fools".

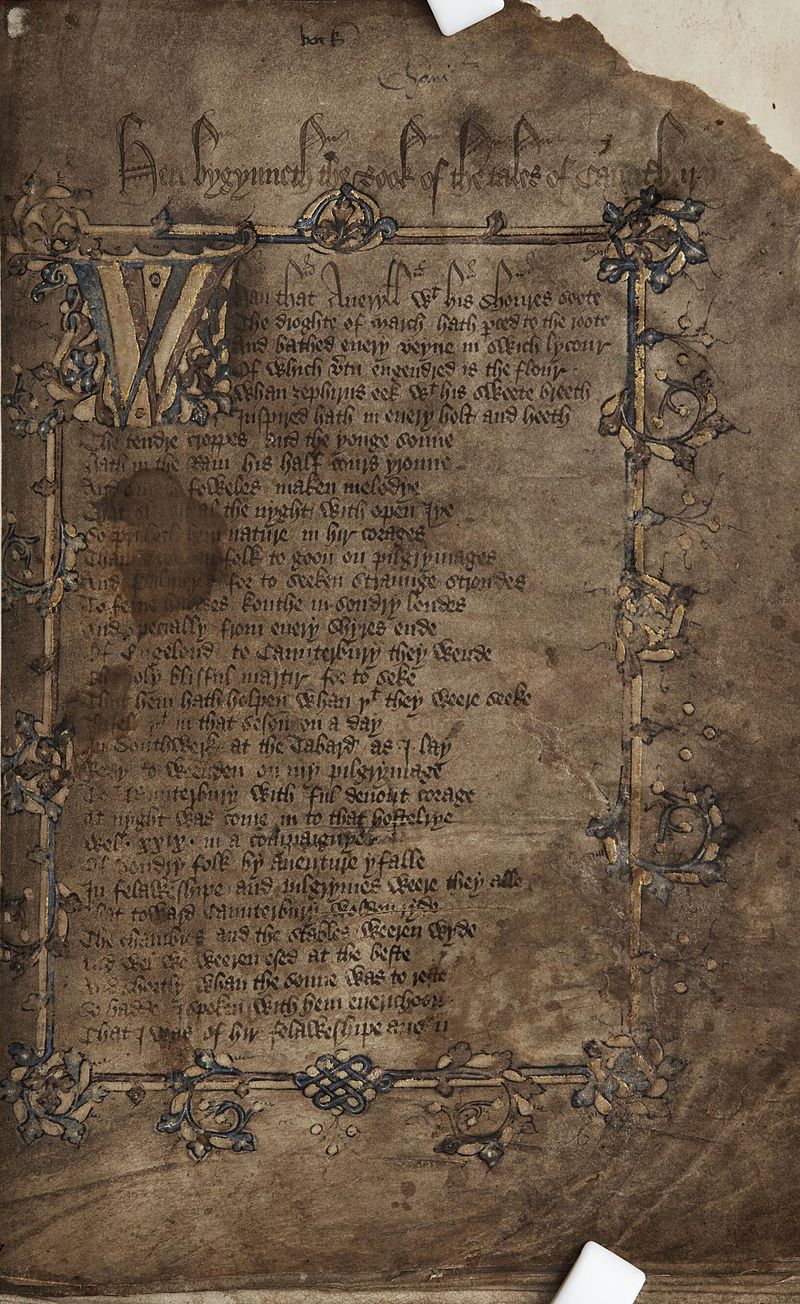

Geoffrey Chaucer known as the Father of English literature is widely considered the greatest English poet of the Middle Ages. He was the first poet to be buried in Poets' Corner of Westminster Abbey. His “The Canterbury Tales” is a collection of 24 stories that runs to over 17,000 lines written in Middle English by Geoffrey Chaucer between 1387–1400 (exactly in 1392) contains the first recorded association between April 1 and foolishness. In Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, the "Nun's Priest's Tale" is set Syn March bigan thritty dayes and two. Modern scholars believe that there is a copying error in the extant manuscripts and that Chaucer actually wrote, Syn March was gon. Thus the passage originally meant 32 days after March, i.e. 2 May, the anniversary of the engagement of King Richard II of England to Anne of Bohemia, which took place in 1381. Readers apparently misunderstood this line to mean "32 March", i.e. April 1. In Chaucer's tale, the vain cock Chauntecleer is tricked by a fox.

In 1508, French poet Eloy d'Amerval who is a poet of the Renaissance. He spent most of his life in the Loire Valley of France. From his poetic works, especially his enormous 1508 poem “Le livre de la diablerie”, it can be inferred that he knew most of the famous composers of the time, even though his own musical works never approached theirs in renown. He referred to a poisson d’avril (April fool, literally "Fish of April"), a possible reference to the holiday.

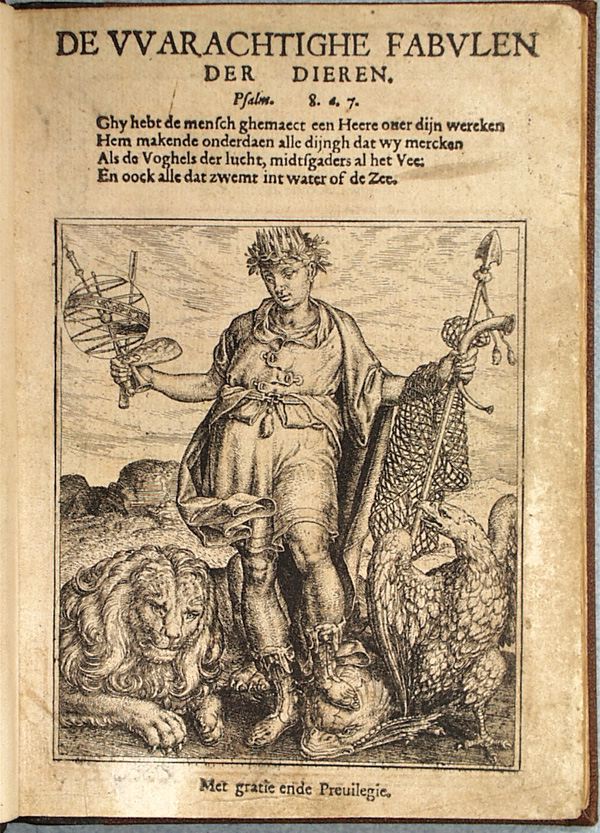

In 1539, Flemish poet Eduard de Dene wrote of a nobleman who sent his servants on foolish errands on April 1. In 1686, John Aubrey an English antiquary, natural philosopher and writer. He is perhaps best known as the author of the Brief Lives, his collection of short biographical pieces. He was a pioneer archaeologist, who recorded (often for the first time) numerous megalithic and other field monuments in southern England, and who is particularly noted as the discoverer of the Avebury henge monument. He referred to the holiday as "Fooles holy day", the first British reference.

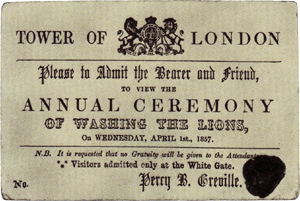

On April 1, 1698, several people were tricked into going to the Tower of London to "see the Lions washed". In the Middle Ages, New Year's Day was celebrated on March 25 in most European towns (just as the Kazakh New Year – Nauryz, which is celebrated 21-22 of March). In some areas of France, New Year's was a week-long holiday ending on April 1. Some writers suggest that April Fools' originated because those who celebrated on January 1 made fun of those who celebrated on other dates. The use of January 1 as New Year's Day was common in France by the mid-16th century, and this date was adopted officially in 1564 by the Edict of Roussillon. Édit de Roussillon - was a 1564 edict decreeing that the year would begin on January 1 in France.

During a trip to various parts of his kingdom, the King of France, Charles IX, found that depending on the diocese, the year began either at Christmas (at Lyon, for instance) or on 25 March (as at Vienne), on 1 March, or at Easter. In order to standardise the date for the new year in the entire kingdom, he added an article to an edict given at Paris in January 1563 which he promulgated at Roussillon on 9 August 1564. It started being applied on January 1, 1567. The 42 articles that comprised this edict concerned justice, except the last four, added during the king's stay at Roussillon. It was article 39 that announced a January 1 start date for every year henceforth.

The first mass April Fools' Day took place in Moscow in 1703. The heralds walked through the streets and invited everyone to come to an "unheard-of view." From the audience there was no release. And when, at the appointed hour, the curtain opened, everyone saw on the stage a banner with the inscription: "The first April - do not trust anyone!" This ended the "unheard-of idea".

In the works of many writers and poets from the end of the 18th century there appeared lines about the April Fool's rallies. For example, Alexander Pushkin wrote in a letter to Anton Delvig (October-November 1825):

“Eyebrows the king frowning,

He said: "Yesterday

The storm fell

The Monument of Peter".

He was frightened:

"I did not know! .. Is it true?" -

The Tsar laughed:

"Happy First April, brother!”

Alexey Apukhtin wrote in his poem "The First of April" (1857):

“Happy day! For a long time

The custom is patriarchal

At us: and to lie, and any nonsense

Today, everything is brimful.

Although a lie, then, incidentally, took root

So good to us in fact,

That every day of the year we have

Partly - the first of April.

...”

References:

- Hopper, Vincent Foster (1970). Chaucer's Canterbury Tales (Selected): An Interlinear Translation. Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 0-8120-0039-0.

- Charles W. Eliot, ed. (1909–1914). English Poetry I: From Chaucer to Gray. The Harvard Classics. XL. New York: P.F. Collier & Son. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- Richard Loyan, "Eloy d'Amerval", The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie. 20 vol. London, Macmillan Publishers Ltd., 1980. ISBN 1-56159-174-2

- Coigneau, Dirk. « Een Brugse Villon of Rabelais? Eduard de Dene en zijn Testament Rhetoricael (1561) [archive] », Conformisten en rebellen: Rederijkerscultuur in de Nederlanden (1400-1650) (réd. Bart A. M. Ramakers), Amsterdam University Press, 2003, p. 199–211.

- Dictionnaire Historique de la France, by Ludovic Lalanne, p. 84, vol. 1, 1877, Reprinted by Burt Franklin, New York, 1968.

- Bennett, Kate (2015). John Aubrey: Brief Lives with An Apparatus for the Lives of our English Mathematical Writers. Oxford: OUP.

- The New American Cyclopaedia: A Popular Dictionary of General Knowledge, p. 493, ed. George Ripley, Charles A. Dana. D. Appleton and Company, 1858.

- Wainwright, Martin (2007). The Guardian Book of April Fool's Day. Aurum. ISBN 1-84513-155-X

- Dundes, Alan (1988). "April Fool and April Fish: Towards a Theory of Ritual Pranks". Etnofoor. 1 (1): 4–14. JSTOR 25757645

- А. С. Пушкин. Собрание сочинений в 10 томах. Т.9. Электронная публикация — РВБ, 2000—2004

- Дню смеха 300 лет, «Вечерняя Москва», № 58 (23616) от 01.04.2003.

Author Akhan Tuleshov

adebiportal.kz - Literary Portal