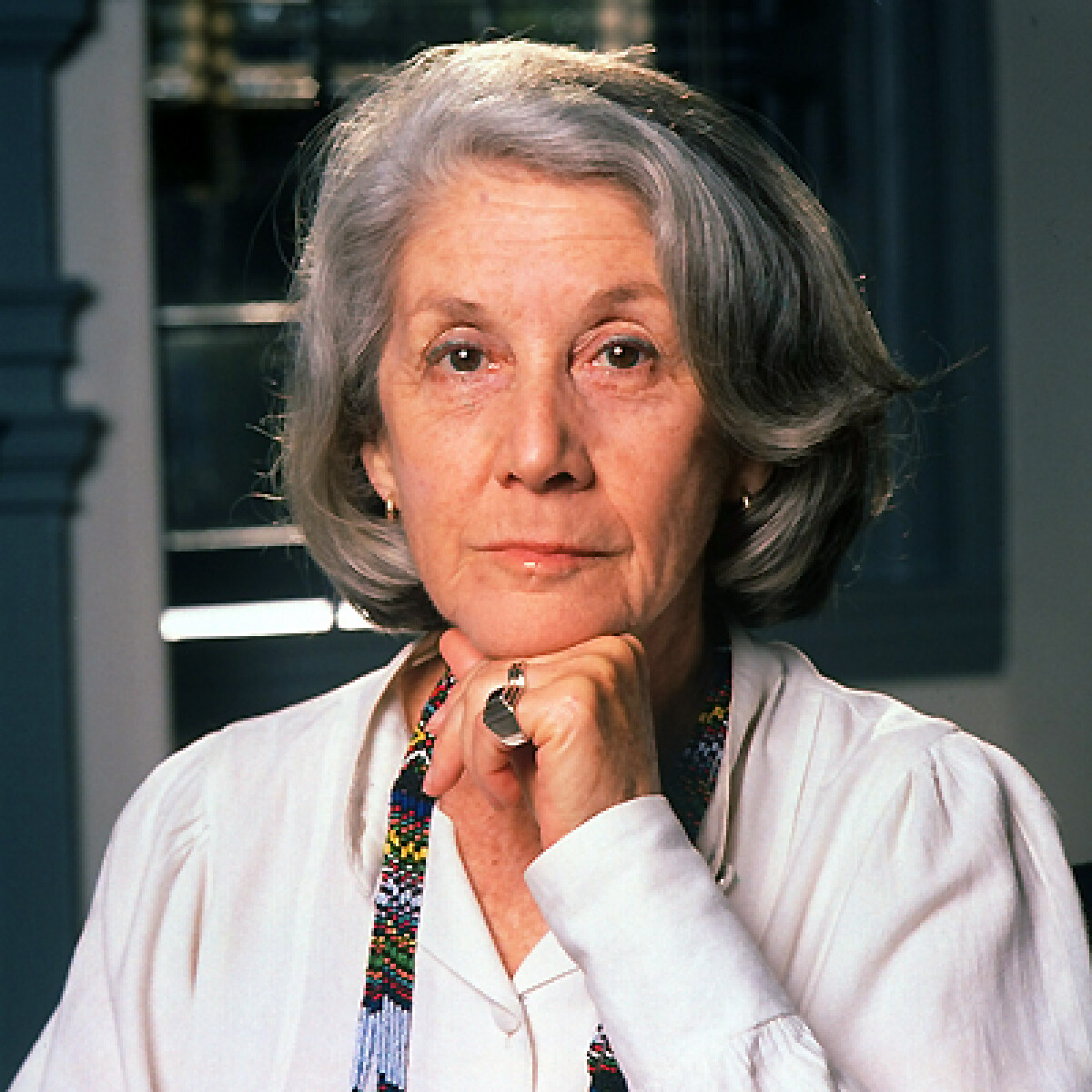

Nobel-prize-winning chronicler of apartheid died peacefully in Johannesburg on Sunday

South Africa mourned one of its literary giants on Monday, with the death at 90 of Nadine Gordimer, a Nobel laureate praised for remaining politically and intellectually courageous until the end.

Gordimer, arguably the foremost chronicler of racial apartheid and the subsequent vicissitudes of democracy, died peacefully in her sleep at her home in Johannesburg on Sunday, her family said. Her son, Hugo, and daughter, Oriane, were with her at the time.

The daughter of a Jewish watchmaker from Latvia and middle-class woman from Britain, Gordimer started writing in earnest at the age of nine and produced 15 novels as well as several volumes of short stories, non-fiction and other works. She was published in 40 languages around the world. Her literary gaze was unsparing on both white minority rule and the governing African National Congress (ANC).

"She cared most deeply about South Africa, its culture, its people, and its ongoing struggle to realise its new democracy," the family said. Her "proudest days", they said, included winning the Nobel prize and testifying in the 1980s on behalf of a group of anti-apartheid activists who had been accused of treason.

During the liberation struggle she praised Nelson Mandela and accepted the decision of his ANC, of which she was a member, to take up arms against the regime. "Having lived here for 65 years, I am well aware for how long black people refrained from violence," she said. "We white people are responsible for it."

Gordimer worked on biographical sketches of Mandela and his co-accused to send overseas to publicise the Rivonia trial in 1963-64. In his autobiography, Mandela wrote of his time in prison: "I tried to read books about South Africa or by South African writers. I read all the unbanned novels of Nadine Gordimer and learned a great deal about the white liberal sensibility." She was among the first people he met on his release in 1990.

More recently she turned her crusading wrath on the ANC itself over proposed secrecy laws that threaten to curb freedom of expression and put journalists and whistleblowers in jail. Three of Gordimer's books had been banned during apartheid. She also remained socially active and was a regular at Johannesburg's Market Theatre until shortly before her death.

At her 90th birthday dinner in downtown Johannesburg last November, she sat next to George Bizos, part of the legal team at the Rivonia trial. He told her: "You are not only a writer, you are a pretty tough woman who stood up to the apartheid regime."

Another speaker paraphrased the cricketer Don Bradman in saying that now she had reached 90, there was no reason why she should not make 100. The petite author, an atheist, shook her head fiercely and proclaimed: "Enough!" The party was entertained by the jazz trumpeter Hugh Masekela, who said to Gordimer: "It's such a wonderful privilege for us to play for you tonight and when we grow up we hope we'll be just like you."

On Monday Masekela, currently in London, said: "She was a dear friend," but declined to comment further.

Tributes were paid from South Africa and around the world. Victor Dlamini, a writer and photographer, said: "I studied at the University of Natal during apartheid and was always struck by how, in the tradition of Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, she was not afraid to tackle the issues of the day. She never had that idea that literature must be pure of the issues of society. She was able to look at the society and write hauntingly beautifully about it but at the same time unsparingly leave you in no doubt who was right and who was wrong."

She remained a critical friend of the ANC after it came to power. Dlamini added: "Unlike a lot of literary figures who gravitate towards power once they win awards, she resolutely avoided the ministers and stuck with her friends. She felt there was no separation between social justice and literary concerns."

Gordimer won the Booker Prize in 1974 for The Conservationist, a novel about a white South African who loses everything, and the Nobel Prize in 1991, when apartheid was in its death throes. But she never lost relevance, Dlamini said. "There was always this sense that once apartheid was dismantled, South Africans would have nothing to write about, but as she showed in No Time Like the Present, history takes a long time to dismantle. The past is in the present." No Time Like the Present, her final book, deals with contemporary South African talking points: its characters suffer brutal crime and complain about the quality of schools.

In October 2006, at the age of 82, Gordimer was attacked, robbed and locked in a cupboard in her upmarket home. She handed over cash and jewellery, but would not part with her wedding ring. Gordimer later said she felt no fear and it was merely her turn to experience violence like many of her compatriots before her.In recent years some black critics scorned her as a "white liberal" whose work was little read by the country's black majority. The ANC government in Gauteng province described her book July's People as "deeply racist, superior and patronising" and banned it from local schools.

Gordimer once said: "We were naive, because we focused on removing the apartheid government and never thought deeply enough about what would follow."

Maureen Isaacson, a literary journalist, said: "She was disappointed with the symptoms of corruption she was seeing. She remained optimistic because she had seen the change and she was hoping things would turn around. She was very positive about the media and felt it should continue doing an excellent job in exposing corruption."

Isaacson had known Gordimer for 30 years and became a close friend over the past 15. She added: "It was rewarding and challenging, She was not indulgent in any way. Her influence on me was focus and discipline. She was always pushing me to greater understanding and clarity. She was just an all round social being; she loved theatre and reading and new talent. She was interested and interesting."

Craig Higginson, a novelist and playwright, said: "She was incredibly generous and supportive to me. She would come to the Market Theatre and stand in a cold corridor at 10 at night to talk to you about your play."

Gordimer was a giant whose influence would be felt for generations, Higginson added. "She was never afraid to say the uncomfortable thing and risk being unpopular for it. She honoured what she believed to be right. She once said she'd made many mistakes in her life but the one thing she was not was afraid. For a small person, she was very powerful."

Gordimer married Reinhold Cassirer, an art dealer who had been a refugee from Nazi Germany, in 1954. He died in 2001 at the age of 93. She had two children, one from a previous marriage.

For Gordimer, art and activism were bound together since birth. "I used the life around me and the life around me was racist," she said in a 1990 interview. "I would have been a writer anywhere, but in my country, writing meant confronting racism."

At her 90th birthday dinner in downtown Johannesburg last November, she sat next to George Bizos, part of the legal team at the Rivonia trial. He told her: "You are not only a writer, you are a pretty tough woman who stood up to the apartheid regime."

At her 90th birthday dinner in downtown Johannesburg last November, she sat next to George Bizos, part of the legal team at the Rivonia trial. He told her: "You are not only a writer, you are a pretty tough woman who stood up to the apartheid regime." Maureen Isaacson, a literary journalist, said: "She was disappointed with the symptoms of corruption she was seeing. She remained optimistic because she had seen the change and she was hoping things would turn around. She was very positive about the media and felt it should continue doing an excellent job in exposing corruption."

Maureen Isaacson, a literary journalist, said: "She was disappointed with the symptoms of corruption she was seeing. She remained optimistic because she had seen the change and she was hoping things would turn around. She was very positive about the media and felt it should continue doing an excellent job in exposing corruption."